There are two ways to begin. I’ll start with the drama.

We exist in a world transformed by climate change, a different planet that I was born on four decades ago (Bill McKibben argued as much in Eaarth fully 13 years ago). The “trillion ton blanket” of greenhouse gases that we’ve burned is already and will continue to refashion weather, coastlines, rainfall, crops, habitats, disasters, and more.

If we put climate change into a larger bin of ecological crisis, then degradation of habitats is surely the most dangerous process unfolding around our planet. Understandably, as terrestrial animals, we focus on deforestation, but don’t ignore the terrifying things we’ve done to the ocean. Deforestation destroys incredible biodiverse habitats, most often through burning felled trees, directly contributing to global emissions totals. Estimates vary, but probably on the order of 2 gigatons of CO2 equivalent every year (Indonesia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Brazil alone totaled that much in 2019). While, of course, the deforestation that is occurring is not done out of pure spite — people are making money out of this endeavor — it’s global harms far, far outweigh the pecuniary benefits that it provides through cattle ranching and palm oil plantation production.

But there is another driver of emissions that produces even more warming effects with little to no benefits to humans: fugitive methane emissions. Between leaks from gas/oil and coal developments, the annual release is about 3 gigatons of CO2 equivalent, about India’s emissions in 2019. This is not even including flaring, which just tries to burn some of the methane on the way out as CO2 does less to warm our atmosphere than methane, although the latter does at least do its damage over a shorter timespan.

So if those are the big two, both often discussed and decried, let me add a third, admittedly smaller, but still gigaton-scale: the Chinese construction sector. I wrote about the carbon implications of China’s real estate binge for the excellent Phenomenal World.

Whenever global demand or internal growth faltered in the recent past, China’s government would unleash pro-investment stimulus with impressive results. Vast expanses of highways, shiny airports, an enviable high-speed rail network, and especially apartments. In 2016, one estimate of planned new construction in Chinese cities could have housed 3.4 billion people. Those plans have been reined in, but what has been completed is still prodigious. Hundreds of millions of urbanizing Chinese have found shelter, and old buildings have been replaced with upgrades.

The scale of construction has been so prodigious, in fact, that it has far exceeded demand for housing. Tens of millions of apartments sit empty—almost as many homes as the US has constructed this century. Whole complexes of unfinished concrete shells sixteen stories tall surround most cities. Real estate, which constitutes a quarter of China’s GDP, has become a $52 trillion bubble that fundamentally rests on the foundational belief that it is too big to fail. The reality is that it has become too big to sustain, either economically or environmentally.

And, connecting the dots:

The carbon

Why do I call this the carbon triangle? Because China is the world’s leading emitter of greenhouse gases, producing around 30 percent of global carbon emissions; the US, at No. 2 contributes 13.5 percent. …

Again much of this construction is not actually producing value as housing or office space. Only fugitive methane emissions and deforestation put more greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere while producing less value than the Chinese construction sector, which means that right-sizing that sector represents an immense opportunity to slash global emissions. To be clear, the ‘value’ here is not meant in monetary terms but instead in terms of services for people, as the IPCC put it, to help us live our lives well. Rhodium Group estimates the stable level of demand for construction in China at 550-750 million square meters annually, which would require another 15-37 percent decline from the level of newly started projects today. …

If residential construction continued to slide to say 600 million square meters, Chinese cement production could fall from well over two billion tons annually to only 1.2 billion tons going forward. Steel could follow a similar path. A gigaton of CO2, 2 percent of annual global emissions, could disappear.

So, to your list of great sources of emissions that serve little purpose, add China’s real estate sector. Governments need revenue, lease land to developers, who borrow to build apartments that have little value as housing but instead are simply speculatively held by those who believe that the government will never let the market crash. So, buildings surround third-tier cities that sometimes remain concrete husks and even if completed rarely become lively centers of community.

The messier, knottier way into China’s tangled land, finance, and real state system is to think about who is serves and why, but also who it leaves out. It’s a tale with history, of development growth models and stimulus, of fiscal deals and debt burdens; it’s a tale of greed.

The Carbon Triangle piece presents much of this picture. Growth becomes the goal following the flop of Maoism. While China’s export-oriented industrialization is the understandable focus of much attention—after all, China rocked the world by adding roughly a billion workers to the global labor supply, upending relations with capital owners and not in the workers favor—investment has mostly been king.

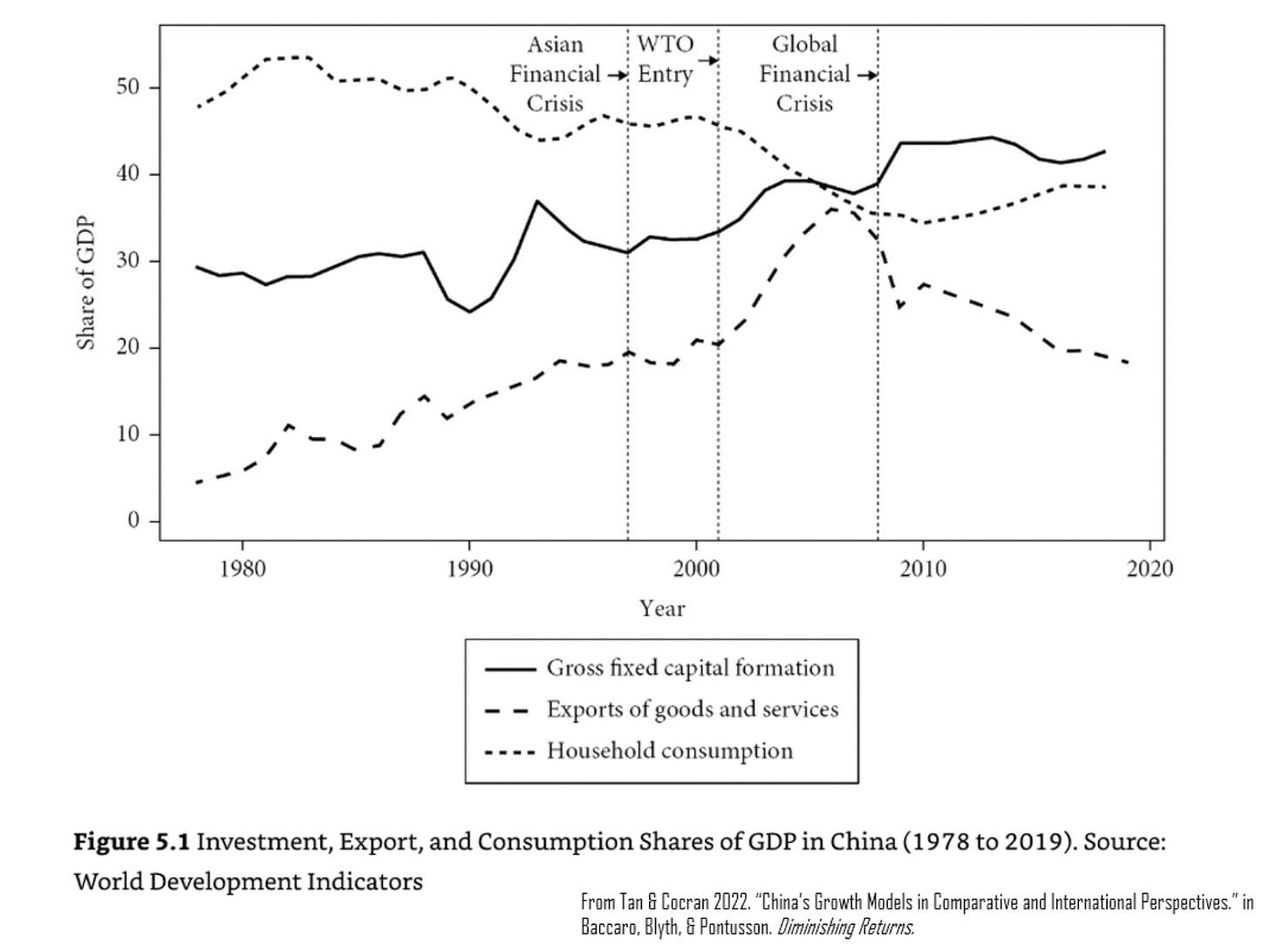

Particularly in moments where other sources of demand ebbed — read the global financial crisis — China built. The graph above, from a great chapter by Tan and Cocran in the excellent volume Diminishing Returns edited by Baccaro, Blyth, and Pontusson, once can see that after the GFC there’s a spike in investment, which then stays around 40% of GDP through 2019. That plateauing might seem to indicate stability, but China’s economy more than doubled in size from 2009 to 2019, meaning that to stay at a steady state of 40% implies more land, cement, and steel than before.

A point that I did not emphasize in the piece is the depths of inequality in the real estate sector. While there are lots of apartments that are empty, that does not imply that everyone has the home that they want. Far from it.

The propertied classes are politically powerful. The laborers that build those houses almost never are able to purchase them and have less voice. The Chinese Household Finance Survey indicates that more than a fifth of Chinese urbanites own a second property and that the #1 use of that property is … vacancy.

Yet there is a vast migrant underclass that will never be able to buy into housing in the major cities. The price to income ratio of China’s biggest cities is deranged, completely disconnected from the labor income of the denizens of the city.

So, this poses a double-bind. The biggest cities are completely unaffordable, making it difficult for laborers to access communities that demand their labor. And changing that can’t really be solved by just more building because properties are snapped up by those already owning property. Taxing existing properties — especially vacant ones — would help push down prices and also represent a viable revenue stream going forward, but the propertied classes aren’t excited about (1) paying and (2) letting the government know how many properties they own.*

*Aside — yes, the argument against the property tax, a real program that would have real advantages for China and is being pushed by Xi Jinping himself, includes the idea that the government of China doesn’t know who owns property in Shanghai. But yes, let’s fret about the omniscient Chinese surveillance state will detect your children’s weaknesses based on geolocation and connections with the TikTok algorithm.

At any rate, while there is certainly vacancy in and around the first-tier cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen…), the real problem of waste at scale is occurring at lower tier-locales. Anonymous provincial second and third cities that plan to be global outposts and build for millions who will never come. The Phenomenal World piece was already trying to do a lot for a 2000 word essay, but analyzing these kind of inter-city differences is exactly where this project is headed.