Some twenty years ago when I was but a young lad, I would run around a beautiful lake on Peking University’s campus in the morning before my four hour Chinese lessons. Then, during the class, I would find myself hacking black gunk into my handkerchief (an affectation that I took from my dad who swears by them but that I’ve dropped). Fifteen years before that, I was going to elementary school in a tiny town that was mostly settled for the purposes of connecting Italian immigrants from coal mining country in the old world with some of it in the new world. Despite what Dunkin Donuts might have you believe, the world has run on coal for most of the past 200 years.

When thinking about the scale of coal China, global context can be helpful. The rather transparently named endcoal.org keeps perhaps the best and most up-to-date records on the global coal industry. While some coal is burned for heat in small scale furnaces for industry or homes (like in Beijing’s winters circa 2000), most coal is burned to heat water to create steam to spin turbines to make electricity. China has 51% of the global operating capacity of coal generation with 1,043,000 MW as of January 2021. The US is #2 with 234,000 MW, and India is right behind with 229,000 MW. No other country comes close to this scale, as Japan is fourth at only 48,000 MW. Indeed, Shandong province alone has more than twice the coal-fired electric capacity of Japan at 98,000 MW.1

So, when the Xiaoying You of the Carbon Brief writes up a nice analysis of a recent paper titled “A plant-by-plant strategy for high-ambition coal power phaseout in China,” first note the scale. Shutting down 11% of the coal fleet can appear like a light lift — in the past two decades, the US has retired plants with about 50% of its current operating capacity. But remember scale — 11% for China is 111 GW, almost what the US retired since 2000 (126 GW). And China itself has already retired 111 GW of capacity since I was running around Beida.2

The research comes out of Maryland’s Center for Global Sustainability with first author Yiyun ‘Ryna’ Cui and is impressive in its depth and sophistication on the climate, pollution, health, energy, and economic factors related to the prioritization and analysis of phasing out coal in China’s electricity grid. The paper’s 16 listed authors and 28 page supplementary appendix attest to the complicated nature of the endeavor including using a specialized version of the Global Change Analysis Model. At its core, the question of “which plants” is answered with the “low-hanging fruit,” of “the oldest, smallest, and most inefficient.” A benevolent social optimizer would likely agree with their categorization and prioritization and I do hope that China fully implements this plan or something very close to it posthaste. But there are some murkier political considerations to be had. We can think of these as distributional, definitional, and discordant (slightly more polite than the other alliterative option here: delusional ).

There are differences in where these “low hanging fruit” are located. In particular, while the phaseout covers 11% of nameplate generating capacity at the national level, some areas would see more sharp supply cuts. Shandong province would lose 18.5 GW of capacity, around 20% of its total, and Hebei, the steel capital of the world, would see a 26% cut.3 Again, that’s a single province closing more coal capacity than is currently operating in Malaysia and Mexico, combined. Poland, which is seen as a coal-dead-ender and spoiler for successful European movement on climate change, only has 30 GW of operating capacity, what Shandong and Inner Mongolia would shut down immediately under this plan. These cuts could undermine grid stability in these areas and could be seen by local officials and communities affected by the changes as unfair. The industries and economies of these provinces have assembled themselves with expectations about the current and forward-looking situation, and they can be expected to react badly to being told that they are behind the times and out of luck.

Last issue (post? newsletter? what is this thing?), I wrote about salty fights between the beachfront and inland property owners of the Outer Banks as an example of existential politics of climate change and conflicts within groups that have generally aligned interests. Similar kinds of conflicts can be expected at every level of these kinds of changes—between provinces, cities, and neighbors. Such complaints will likely be incorporated into calculations of which plants to shut down when. Political voice, or the perceived threat of it, matters even in a relatively closed information environment like China’s.

Second, definitions. To start, we have to talk about waste. The China Electricity Council, the power sector’s trade association, argues that retiring plants too early will produce “waste.” Carbon Brief’s writeup is excellent:

Previous research by the China Electricity Council (CEC) shows China’s coal-fired units have operated for just 12 years so far, on average, and only 1.1% of its units have operated for more than three decades, the typical lifespan of a coal-fired unit. This means that the Chinese coal fleet is much younger than those in the “western world” and harder to retire in a limited time without causing “substantial waste”, the CEC pointed out.

The waste here is financial. It is not coal ash, carbon dioxide, PM 2.5, or other emissions from the burning of Jurassic-era sunlight trapped in sooty old rocks on the order of millions of tons. Financially speaking, coal plants require substantial upfront expenditures as well as fuel and labor costs to operate, and they are investments calculated to (1) produce GDP for local officials interested in hitting quantitative targets and (2) produce profits after X number of years of operation. Shutting plants down before their lifecycle is completed is “wasteful” only if they are being replaced with new replicas. But as the Cui et al paper clearly shows there has been vast improvement in the efficiency of China’s coal fleet with older plants using outdated technologies and much more labor (note this, we’ll return soon) compared with new ultra-supercritical units. Renewable energy, on the other hand, is even more front-loaded than coal plants but has little operating expenses as sun and wind are free. So, again, we are left with the idea that the underlying concern is that asset holders—of the coal plants themselves, of the banks that hold their loans, of the state-owned conglomerates that control these firms—will see their valuable assets zeroed out.

On the labor front, on the other hand, there is another political issue. Shutting down plants that employ more workers and so are more expensive makes economic sense but … ends more jobs and increases the political challenges of the policy. Turning off a robotic conveyor belt generates no political sympathy, whereas making redundant 5000 workers in a given suburb paints a different picture.

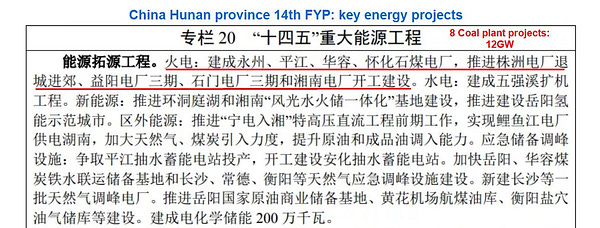

Finally, we get to the discordant notes. Many expressed disappointment with the recent 14th Five Year Plan’s lack of ambition, as I wrote about in the prior incarnation of this blog/newsletter/thingy. It contained no language mandating such an immediate phaseout of coal, and could be summarized as an extrapolation out of current trends on carbon intensity, renewables, and electric vehicles. And while that post suggested that Xi Jinping shared in that disappointment and so perhaps reasons for hope remain, the idea that coal is on its way out without a fight is silly. Carbon analyst Yan Qin tweeted a release from Hunan’s plans to construct 12 GW of coal capacity by 2025.

Hunan argues that energy security, also language highlighted in the 14th Fiver Year Plan, requires it to add more coal capacity. Of course, phasing out coal and building new coal plants are different things. And the idea that one province could add coal capacity equivalent to the Philippines in 5 years is … not decarbonizing China.

This discussion is not meant to criticize the excellent work that Cui et al have done in any way. It is just to note that the politics of a given situation does not always so easily line up with “what is best” or what is right. We will all be running around in circles on these issues for a long time. Ending China’s coal addiction will be hard, but what is politics but the slow boring of hard boards.4

In fact, the fact that the Coal Tracker uses MW instead of GW is concession to the reality that many countries just don’t operate at the GW scale in coal. We’ll switch to GW for the rest of this post.

All statistics from the Coal Tracker databases.

I’ve heard that this new translation of Weber is excellent.

Existential politics of climate change in China is an important research topic!