Comfortable Lies and Inconvenient Truths

Confronting difficult implications and realities of the green tech revolution

Since people seem to have enjoyed my last post and the WIRED piece that it was based on, as ever, I’m tempted to dive deeper.

Before that, though, since I’ve received multiple requestions on this point, I must make a statement. ALERT to media outlets that are looking for someone to confirm that, contra the President of the United States, feel free to quote me: China does install wind turbines on land and sea, and they do generate electricity that helps power their society. I have seen them in person in Ordos, near Shanghai, and a dozen other places in between. They are real, and they are spectacular.

I was on KQED’s Forum (live radio in 2026!) last week and appeared on the Science Friday podcast as well. Go listen if you prefer your analysis in audio.

Ok, now that we’ve taken care of that, down to business.

Why did I write Hot, Cheap, and Out of Control or China’s Renewable Energy Revolution Is a Huge Mess That Might Save the World? What’s the take away? Or the policy prescription that follows from its analysis?

At a basic level, I wrote them because I think that they are true even if they are not the easiest to sit with. We live in times when silos are difficult to spot or escape from. It is nothing to just wake up and read the feed that prior iterations of myself has curated (with extensive algorithmic assistance) and feel informed (and enraged and entertained and heartbroken and everything else). It takes effort to confront parts of our beliefs that may not stand up to strong scrutiny. There are many comfortable lies and inconvenient truths out there. I’ll hold off on my Mark Carney/greengrocer takes, but that notion of living within lies is a real one.

There are obvious lies or falsehoods — like Trump’s windmill crack or denial of climate change. Avoiding these should be easy for broad, big picture topics. But once one dives into the details of a specific legal/financial/social/economic/political situation, things can get messier.

By deeply tying the idea of the green tech revolution to the notion of chaos, I’m trying to provoke a reaction. To shake off a bit of complacency. Good things do not always go together. If and when they do, it might not always be in the way that one expects.

In that spirit, some takes.

Climate and Affordability

I was recently at an event with this title in DC bringing together policy people to discuss possibilities to move forward. There are many ways in which the current administration’s attacks on clean electrification are bad for both climate action and affordability. We mostly settled into railing against these kind of stupid policies (comfortable) instead of venturing into the more dangerous territory of tensions between these twin poles of 2026 political rhetoric on the left.

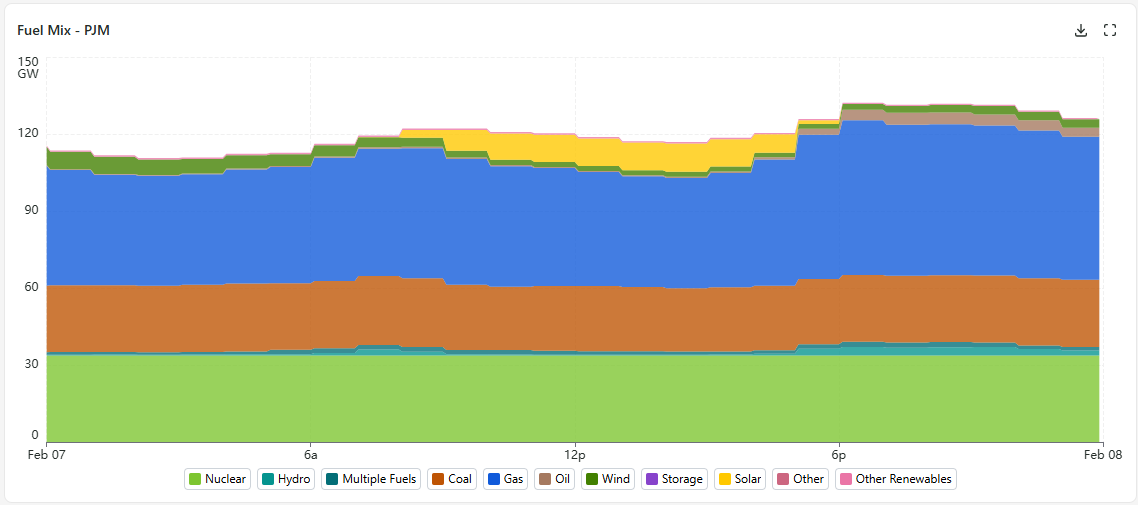

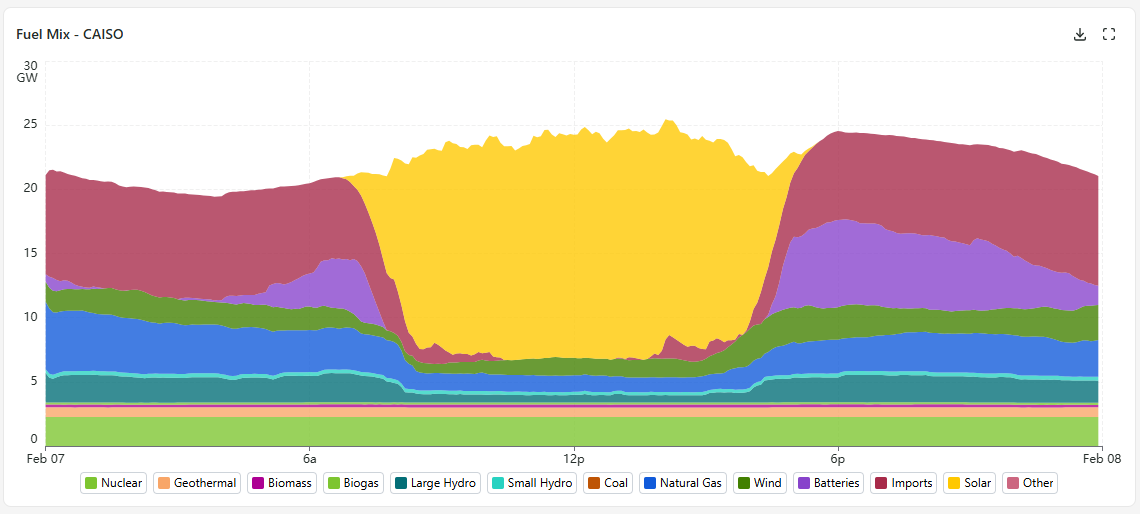

It happens to be the case that the meeting took place in the USian national capital, which is on the east coast of North America, where a good many of my fellow Americans reside. If offshore wind isn’t happening at all or cheap, then providing clean electricity to this important swath of the people and economy is tough. Looking at the Grid Status pages for PJM or ISONE regional transmission organizations shows how far behind they are compared to California or Texas. The thing is these regions suffer compared with CA and TX in resources. While they certainly should put up more solar and more wind, they are not blessed with the vast tracks of relatively empty1 land that solar and wind require.

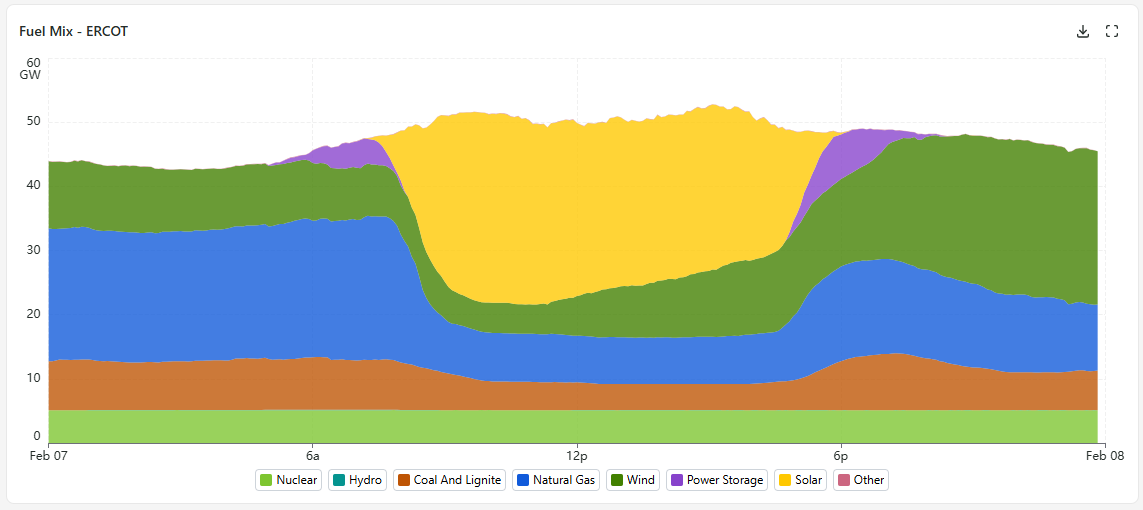

I mean, just look at PJM (Upper Midwest) from Feb. 7 compared with ERCOT (Texas)

The PJM region abuts the MISO grid, and MISO is full of plentiful renewable electricity, especially wind. Transmission lines could bring some of that power to the east coast where it is desperately needed, but Sen. Josh Hawley and Trump didn’t like the “Grain Belt Express” line that tried to turn that idea into a reality and cancelled $5 billion funding for the project. It’s another example of an easy dual win for climate and affordability that Trump killed, but alas. Most people would prefer not to have a powerline built near their home, but if it saves you hundreds of dollars a year and can bring 5 nuclear plants worth of clean electricity to your state, it has some real value.

We’re still burning oil (!) in the Northeast and New York to generate electricity in the winter. Shutting down nuclear plants was a mistake. Connecting powerlines, including from HydroQuebec, are good ideas. But there can be thorny questions here too. Should the northeast have new LNG (liquid natural gas) hubs or connect to other gas infrastructure? These are way better than burning oil, which people currently do in their homes for heating plus the grid’s use. We need to shift away from all of this fossil infrastructure, but what about the next decade? Oil? Really?

To draw this out one more step, an electrified future is going to remake our electricity grid. Remember that we build the grid assuming that everyone can turn things on at a whim. Most grids in the US are summer peaking, because AC is electrified whereas most heating isn’t. But with EVs and heat pumps, grids will shift to having winter peaks. And they will be rough, especially for a clean grid. The sun is barely up, and often cloudy, snow piles up on solar panels, and so on. Heating can take a lot more energy than cooling in these places — consider the distance between a comfortable 72 and the 0 degrees outside that one might see in December, and compare that with a scorching 100 degree day and 72. Think how much shorter your range is in an EV in the winter than the spring. There are already some good programs like Vermont distributing batteries, but more is needed. Improving the efficiency of homes is a must.

Even here, though, the perfect can be the enemy of the good. There may be tradeoffs between more stringent new housing requirements and building more housing, especially in dense areas. To be clear, we don’t want lots of new energy profligate housing, but new houses (especially multifamily construction or row houses that share walls and warmth) often are replacing an existing housing stock that is older and even worse in energy terms. A similar discussion of stringent standards and safety sometimes takes place with the “single stair” debates, where advocates suggest the need for double-staired apartment buildings for fire safety is ridiculous waste of space that could provide better apartment designs with more space/windows. These debates get technical, I suppose, but few dispute that single-family homes are far more dangerous than new multi-family homes of almost any variety.

The hardest bullet to swallow under this heading is how far we are along in the solution space for clean electrification at affordable cost. Mark Jacobson (who was on the KQED Forum episode with me) has long advocated for 100% water, wind, and solar as a solved problem. His twitter presence consists mostly of posts about how California’s grid was fully powered by these technologies (plus batteries) for some portion of the day. Yet as the above discussion suggests, we’re not all in California, and even California isn’t yet at 100% clean.

There’s an unfortunate piece of legal history where scholarly criticism of Jacobson led him to pursue a lawsuit against the critics. RetractionWatch and Columbia’s Climate Litigation database have the details.

Jacobson is the most referenced source in Bill McKibben’s new book, Here Comes the Sun. I really enjoyed the book and have hopes of writing a review of it either alone or with others in the pile. Jacobson’s sunny analysis jives with McKibben’s activist call for more action, but while I’m very hopeful that renewables will get us most of the way to decarbonization, of the grid and of a lot of other things too (though not agriculture), there are hard parts.

There’s what seems to me to be a mistake/confusion in McKibben’s book about Dunkelflaute, the German word for dark doldrums describing periods of little wind or sun. On p. 59, there’s a quote suggesting a 4 hour battery can get a grid through a Dunkelflaute. And, obviously, that could be true for a short period with enough charge in a big enough battery. But the usual way that we talk about dark doldrums are on the scale of days, not hours. This discussion of Dunkelflauten mentions 30 and 54 day durations. And battery economics can fail if we are building them out to be used only once or twice a year. This reality of our climate system is a key reason why decarbonizing the grid with existing tech ninety-percent isn’t too hard, but the final 10% gets sharply more expensive. Storage (batteries?) that can shift energy from summer to winter, new clean firm technologies like enhanced geothermal, nuclear, etc all will help fill in the gaps without emitting more carbon, but figuring out those details matters. It doesn’t stop us from pursuing more wind, water, and solar today. We should! And rapidly. But it is important to remember that the final pieces remain a puzzle.

Minimum Viable Scale

Here I just want to share a link and make you go read the whole thing. It’s a paper in Science.

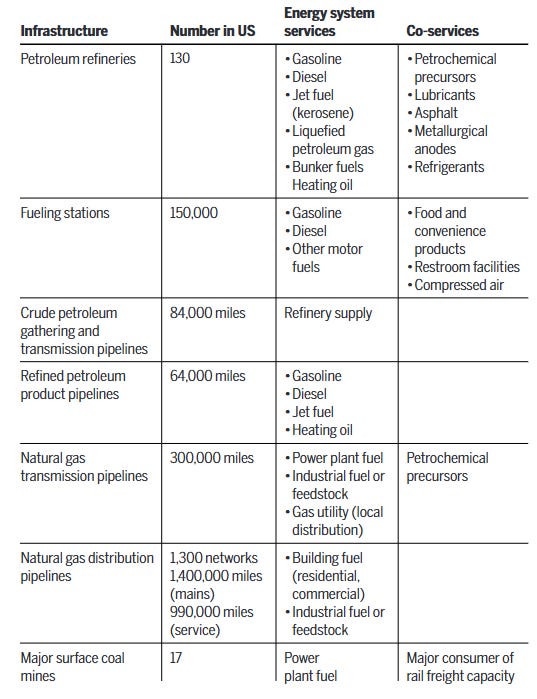

Joshua Lappen & Emily Grubert. Fossil energy minimum viable scale. Science 391, 449-452 (2026). DOI:10.1126/science.aea0972

Here’s the abstract:

The nascent global energy transition involves two parallel, mirrored processes: the retirement of existing fossil fuel-based infrastructure, and the widespread deployment of alternatives in its stead. Most energy transition research and policy have focused on the latter process of development, adoption, and buildout. Far less attention has been paid to the challenges and emergent behaviors associated with the decline of legacy fossil energy systems. We identify a risk of collapses in service availability as specific elements of fossil infrastructures reach what we term “minimum viable scale,” a level of throughput past which existing physical, financial, and managerial infrastructures can no longer effectively operate as expected. We establish a framework of different types of constraint that can impose a minimum viable scale and identify such constraints in several example fossil systems within the US. Evidence of widespread minimum viable scales should motivate a paradigm shift in system and decarbonization planning.

Transition is not a simple linear winding down of things like we might hope or model it to be. It is lumpy with particular facilities and assets vulnerable to movements that could produce non-linear responses.

Look at this.

Just as solar in China is spiraling from success to success, so too can fossil systems quickly go from working to collapsed. The difficulty, of course, is that we need these things, at least for now. We need to plan for how we will go from 130 refineries to 100 to 50 without things completely breaking. We need to plan for how to shift home heating away from gas towards electricity without breaking cities/utilities/consumers with bills as death spirals arrive.

Given that I mostly think about China, I came out of reading the paper and my own analysis thinking that coal as backup is actually desirable economically (if not ecologically). Compared to oil where refining and gas where distribution and transmission pipeline infrastructure are complicated interlocking systems to unravel, coal is just a rock that sits where you put it. It doesn’t ooze into the ground or evaporate into the atmosphere.

Battery Cannibalization

I already wrote about the excellent book The Price is Wrong for this humble newsletter.

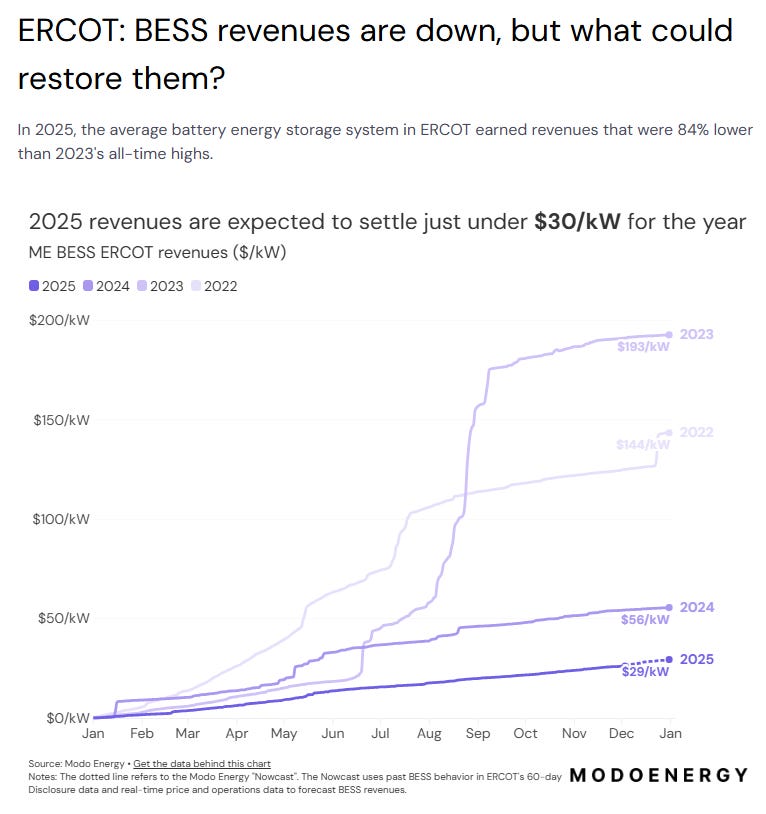

My main complaint is that the price cannibalization of solar that he describes is partially fixed by batteries. Well, ERCOT returns with some mixed news on that front. Batteries seem to be cannibalizing their own revenues.

The story makes clear that part of this is weather. Extremes push the grid to higher prices, which batteries arbitrage, generating revenues. And last year was pretty mild in Texas. But the larger story is a good one that hurts a bit. The presence of batteries have stabilized the grid. This is amazing! Yet this benefit is not yielding great returns to the owners and developers of these batteries. Already deployed batteries are one thing, but for true decarbonization, we’ll need a lot more batteries (even to deal with the day-to-day fact of nightfall, let alone Dunkelflaute). If we’re seeing revenues crater now, what kind of pricing systems will we need to innovate/plan for moving forward?

China is asking the same questions and needs to figure out good answers that work out for everyone.

Good News on the Farm?

There’s a whole discussion about whether economic development can depend on the service sector that I was hoping to also include, but we’ll save that for the Shared Prosperity in a Fractured World review.

Let me end with a twist. Rather than just dwelling on the reality that all good things don’t go together, sometimes there are pieces of the story that fit surprisingly well together. The key example here is agrivoltaics. Putting solar in agricultural fields can be helpful! For agricultural productivity. For animal comfort. For soil health.

‘Agrivoltaics is not just a land-sharing concept, but a systems-level solution to some of the world’s most pressing challenges’

In Ordos, they hope that the panels can help reduce desertification. And it makes sense why it might turn out that way. Farmers in Maryland and Pennsylvania might find out that they can power PJM with solar without killing their crops. Good things can happen. We need to keep our eyes open to the messy reality around us, for good and ill.

Be well, safe, and true out there.

In a conversation with a radio producer, there was an assumption that China could build things in a way that we can’t in the US because of “animals in the desert.” And, of course, no place on this blue marble is “empty” but we have to think about tradeoffs. And solar in most deserts seems like a reasonable one to me. See below for a bit more about this supposed tradeoff twist in a positive way with agrivoltaics.