The passage of the IRA has exposed conflicts within the US climate left as green growth advocates praise the bill while others more tilted towards environmental justice or insistent on cutting back on capitalist consumption react lukewarmly. Divisions, while obviously uncomfortable, suggest that things are at least happening — movements are easy to unite when they are completely sidelined by the powers that be. Now that the US is finally taking some serious actions at the national level, the different prioritizations and theories of change are becoming clearer.

Three weeks ago, the Biden administration looked as though it was doomed to failure. To the already worrisome news of inflation at fifty year highs and approval ratings below 40%, Sen. Joe Manchin announced (for the second time) that Biden’s principal piece of legislation would not move forward. The climate community literally cried and railed at Manchin. The Biden administration had failed.

While we may never really know what changed Manchin’s mind — the best sourcing suggests a conversation with Sen. Coons led Manchin to imagine himself as a heroic baseball player hitting a homer in the bottom of the ninth inning — the result is that the game has changed. The with VP Kamala Harris breaking a 50-50 tie to ensure passage, the Inflation Reduction Act1 had made it past “history’s greatest obstacle to climate progress.”

The always excellent Volts newsletter by David Roberts had Leah Stokes and Jesse Jenkins on to go through many of the particulars. They expressed real pride in the climate provisions of the bill which are quoted at $369 billion, while acknowledging that getting Manchin’s vote involved costs.

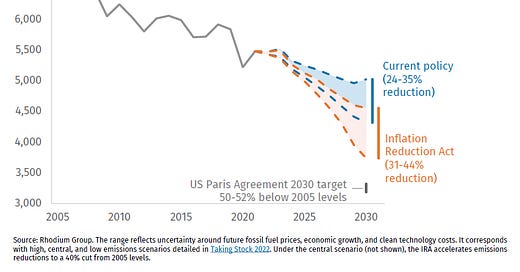

Modeling from the REPEAT Project, Energy Innovation, and Rhodium Group all suggest passage of the bill would lead to US greenhouse gas emissions to fall by 2030 to about 40% below 2005 levels.

Pushback

Despite complete opposition from every last Republican senator, for a climate bill, the IRA had some surprising supporters, including oil executives delighted that more federal lands will be opened up for leasing and some pipeline projects were expedited.

The Center for Biological Diversity put out a press release, Manchin Poison Pills Buried in Inflation Reduction Act Will Destroy Livable Climate. The team behind Don’t Look Up (which I discussed here), Adam McKay and David Sirota, continued their less than sharp climate politics with some dumb tweets. More compelling is the following thread from Green New Deal progenitor Rhiana Gunn-Wright:

She lays out some of those harms: “whether that’s fossil fuel leases or the mountain valley pipeline or permitting reform or technologies that directly and indirectly harm frontline communities or tech that will likely be exploited to prolong our dependence in fossil fuels –” and “it helps lock-in a dependence on cars, a dependence on environmental racism, and a dependence on extractive industries that does very little to move us towards a more just economy with new balances of power.” Similar arguments are offered by Kate Aronoff — The Manchin Climate Deal Is Both a Big Win and a Deal With the Devil — and Yessenia Funes — The Fight to Stop the Inflation Reduction Act’s Fossil Fuel Giveaway.

Over at Slate, Jordan Weissman wrote about this divergence in Why Internet Leftists Are So Pissed About Democrats’ Historic Climate Bill.

Weissman lays out four ways to reduce emissions:

• It can put a price on carbon, using schemes like a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system.

• It can simply force businesses and utilities to emit less via regulations.

• It can try a supply-side approach by shutting down the development of new fossil fuels, in order to increase their costs.

• Or, it can just throw money at the problem by subsidizing cheap renewables so that they take over the market.

The IRA is resolutely in the fourth camp. It is an all-of-the-above energy bill that throws money at renewables and other pieces of the energy transition. Money is directed to consumer electrification, to EVs, to production of renewables, and so on. Weissman argues that the bill is “a rebuke to Washington’s technocratic class” that pushed for carbon pricing or emissions trading as much as it is to those focused on pure regulatory or supply-side approaches, which is where most of the left-criticism is coming from. Stopping pipelines and protecting areas directly affected by digging and pumping fossil fuels out of the ground and then breathing in the sooty fumes after they’ve been burned have been key issues for the environmental justice movement.

I have a difficult time understanding how the provisions in the IRA lock in car dependence other than by omission. The lack of funding for e-bikes (merely the greatest transportation technology on earth), social housing, public transportation, and a thousand other delights etc. is noted and lamented, but of course the status quo didn’t have those things either. The actions in the bill that are more directly concerning are pipeline approvals and expanding leasing. These imply additional fossil fuel infrastructure, and scientific assessments have been clear that keeping warming below 1.5C/2C entails ceasing new fossil fuel infrastructure, as Genevieve Guenther pointed out in this thread.

So, the crux here is this: opening up more land for oil exploration and smoothing the path for more pipelines is obviously not ideal climate policy, even if it was the magic dust that let this bill pass rather than fail. And even these critics (beyond the Don’t Look Up crew) all tend to agree that passage of this act is preferable to its failure. (And remember, this thing is not law yet — it still awaits House votes and Biden’s signature!)

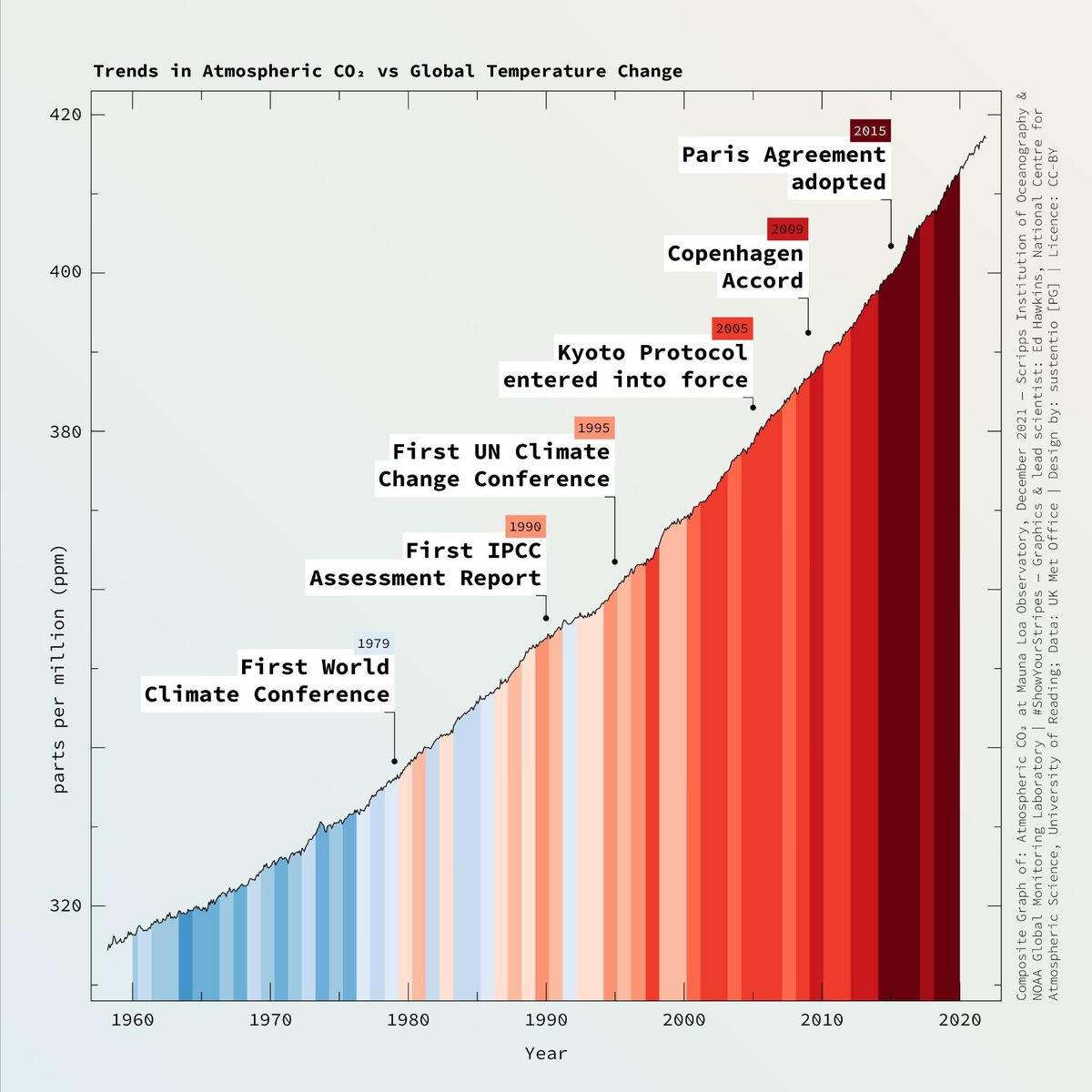

When pushed, often this kind of a graph will come out, showing how global progress is not happening, despite all of the shifting away from coal and rapid decline in the cost of renewables.

Timothée Parrique, an editor at degrowth journal, tweeted this, saying “40 years of blah blah blah.” But this is looking at global stock of CO2 in the atmosphere, which is indeed growing and temperatures are rising. But look at the US emissions chart from Rhodium again.

The US has already cut emissions over a gigaton a year over the past fifteen years.2 More needs to be done and faster, but the idea that nothing is happening is not right. Relatedly, the idea that we’re so close to cutting down the fossil fuel industry to nothing and that supply restrictions will be enough to push up prices and reduce consumption without massive backlash needs reexamining given the past year.

Two more points, on efficiency and perspective.

I think that, interestingly, the supply-side restrainers are actually falling into a similar trap to the carbon-pricers: there is a focus on the most efficient paths rather than the most plausible paths. And, obviously, it is hard to argue against efficiency. Yes, from a planner’s perspective, optimal allocation of energy services could be completed without any additional investment in new fossil fuel-related infrastructure. However, the actually nitty gritty of the energy transition is not so simple.

Take China. How should we think about its energy system in 2022? There are two dominant facts that readers of this newsletter are almost certainly familiar with by this point: (1) an absolutely incredible amount of renewables are being deployed there and have been over the past five years and (2) it remains an energy system with coal at the backbone and is the locale where almost all of the global investment in new coal plants is happening. David Fishman of the Lantau Group just published an excellent FAQ about China and coal. After explaining that many of the planned coal plants are being canceled rather than constructed and those that are built are running at capacity factors under 40%, he asks the key question:

Does that mean it’s more important to look at coal consumption than coal-fired capacity when considering the climate impact of adding coal plants?

ANSWER: Perhaps it feels like we’re leading the witness here, but yes, exactly. The nameplate capacity of fleet of generation units, matters far less than how much power they actually generate. Put another way, this is the difference between GW and GWh.

China is building new fossil fuel infrastructure — coal infrastructure at that! — but it is also powering the renewable transition in production and deployment terms, lowering global prices on these commodities.

Is this efficient? Compared with batteries or other storage technology, I’m skeptical (especially if we model in learning curves and cost declines for these clean technologies), but it is comfortable and familiar for Chinese officials and for Chinese businesses to further construct a system that depends on coal, a resource that China has extensive reserves of domestically and has powered its prior growth. The question that concerns about “stranded assets” come to is: who is going to pay for these fossil fuel investments that aren’t going to be used anymore? Are we going to buy out coal plants? People that built this stuff when everyone told them not to? How is it going to feel to do so? Are we going to pay the oil companies to leave their oil and coal and gas in the ground? These kinds of transfers are going to be a mess, economically and politically.

I think that this back and forth points to three main flavors of activism in the US climate left: the green growthers, the environmental justice advocates, and the degrowthers. The political class of the United States seems to have increasingly accepted the arguments of the first group, acknowledges if not actually compensates and protects communities advocated for by the second group, and absolutely dismisses the third group. This post has already taken too long, so I’ll leave my thoughts on the possibilities and limits of green growth/capitalism and degrowth in China and elsewhere to later.

Finally, the US isn’t everything.

As I have said over and over, here and elsewhere. The climate story today is a China story. China represented 33% of carbon emissions in 2021. Its dynamics will shape the short-term trajectory of carbon concentrations in the atmosphere more than anything else. The climate story of the next two decades is the story of the developing world. Whether that’s the story of the Latin American climate left, or of India/Vietnam/Indonesia choosing solar over coal (or the opposite), and of the development and energy choices of Nigeria, Ethiopia, the DRC, and other African countries….

My strong preference would have been for the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to be the Decrease Inflation Program (DIP) to match the semiconductor industrial policy bill that had also just passed the Senate. CHIPS are always better with DIP.

This probably ignores at least some land use and land cover emissions because … these kinds of models usually do although IRA does include some sequestration/reforestation (potentially boondoggles) funds unless Sinema nixed them and I missed it.