I hope you and yours are well during the 4th wave of the pandemic in the US. It’s been quite the hiatus, during which I’ve published a piece on COVID-19, “A Plague on Politics? The COVID Crisis, Expertise, and the Future of Legitimation,” in the American Political Science Review (co-authored with the impressive Michael Neblo) and relocated to the greater greater Washington region for the year for a sabbatical. There will be more COVID to come (I mean in the newsletter, but I suppose it’s true for the world at large as well), but I wanted to jump back to the other crisis, climate change.

Climate change has been in the news, which usually does not bode well for people. The IPCC made a major release with its sixth assessment report from Working Group I. Now, Working Group I is the physical sciences group, and I’m a political scientist, so I’m going to leave commentary on it to others. Disasters super-charged by climate change abound, including the deadly flooding of Henan and Germany, explosive fires burned British Columbia, the Western US, and Earth experienced the the hottest month in human history in July.

However, instead of staring at the fires, I’m going to write about solutions. Now, to be clear, I’m going to write about how one tool for solving climate change is getting stuck in a blobby quagmire, and in order to understand what’s going on, I’m going to take you into the theoretical quagmire of international order.

Nearly every academic article or think tank report that uses the term includes a section on “what is international order” — see this piece by Michael Barnett, this Rand study, or the 75th Anniversary special issue of International Organization on the theme. Barnett writes “International order regards how rules, institutions, law, and norms produce and maintain patterns of relating and acting.” In their introduction to the special issue, Lake, Martin, and Risse include this interesting figure in their definitional discussion:

The use of a Venn diagram is a bit confounding as these different orders represent levels of depth of infringements upon sovereignty (“ultimate authority over territory”) that states are willing at accept in different orders. But the reality here is fuzzy, as states pick and choose actions or justifications from these different orders at different moments across different issues.

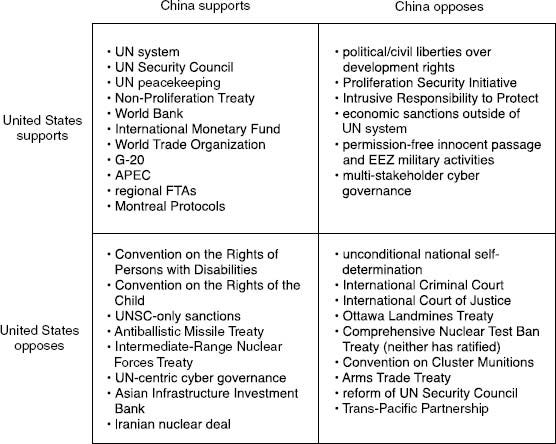

As it happens, Jessica Chen Weiss and I have the last article in that special issue, “Domestic Politics, China’s Rise, and the Future of the Liberal International Order,” where we attempt to answer “how will China’s growing power and influence reshape world politics?” We put forward a framework highlighting two domestic variables — centrality and heterogeneity — to help account for China’s varying acceptance, reluctance, and revisionism with aspects of the international order. In a 2019 article in International Security, Johnston argues that international order is better conceptualized not as a single coherent system but rather as the emergent properties of state-level interactions in different domains. He offers this 2x2 to show how assessing China’s revisionism at the system level from the US perspective to is hard to calculate.

Rather than an international order, many may exist simultaneously. As Johnston puts it:

Thus, there are arguably simultaneously existing emergent properties, and to aggregate them into one U.S.-dominated liberal order misses the tensions and contradictions across different clusters of activity. To paraphrase Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye's notion of “issue-specific power,” there are likely to be different, even contradictory, “issue-specific orders” operating at the same time, in the same geographical spaces, and involving the same states. In some of these orders, the emergent property may be liberal institution building (e.g., a liberal trade order or a pooling of sovereignty among liberal states). In others, it may be balancing (e.g., a realpolitik military order). In still others, it may be aggressively building hierarchy (e.g., a hegemonic ideological order). To the extent that any particular order is internally contested, this is a measure of the degree of order.

In short, it is useful to start with the assumption that there is no single international order that defines whether a state is a challenger/revisionist or not. It seems likely that the number and types of orders existing simultaneously is an empirical question. As an inductive first cut, I propose that there are at least eight simultaneously existing orders in different issue areas. Some of these are dominated by liberal institutions and rules; some are not inherently liberal; some are contradictory; and some are highly contested internally. I expand on these possibilities below.

Johnston puts these eight forward: constitutive order, military/coercive order, political development order, social development order, international trade order, international financial/monetary order, international environmental order, and the international information order. His descriptions acknowledge tensions between the orders, such as between responsibility to protect (R2P) and sovereignty, but does not foreground them. 1 In the end, Johnston’s piece effectively eviscerates the idea that we can think of a state’s relationship to the order as slotting into a status quo vs. revisionist binary.

But even this understates the complexity of the situation. The boundaries between these orders are porous and shifting. Take for instance China’s renewable energy subsidies. That renewable energy became cheaper than coal, then became the cheapest choice for new electricity generation, and then became even cheaper than running existing fossil plants in many/most locations and the cheapest electricity ever is the biggest source of optimism amongst the climate conscious.

How did this happen? Research, subsidies, and mandates from governments. Gregory Nemet’s 2019 book How Solar Became Cheap seems like a reasonable place to go.2 Here’s a figure from his website.

China’s scaling up of the solar industry did not start the learning curve, but it pushed low-cost production to a scale that actually has a shot at remaking the global energy system and mitigating climate change.

The changing economics of renewables, especially solar PV, allows for the possibility of mitigation with much less economic dislocation and changed the global discourse on policy. The environmental order, then, greatly benefited from Chinese subsidization of renewables.

However, from the trade perspective, well…. The US under Trump unilaterally initiated global tariffs on solar (and washing machines) in January 2018, following prior complaints that Chinese producers received subsidies, sold their products for less than fair value, and then shifted the final stages of manufacturing and assembly outside of China to avoid bilateral spats.

China responded through the WTO.

The back and forth continues, with an additional twist that brings in concerns about human rights and forced labor.

We’ve now, finally, reached the news story that prompted this newsletter in the first place.

Escalating U.S.-China Solar Rift Threatens Biden Green Goals

As ever, the devil is in the details. The US solar sector is not small in employment terms, but mostly installs imported panels and cells. These firms had prepared for the Biden administration to impose restrictions on polysilicon from Xinjiang because of human rights concerns, as polysilicon is a core piece of cells. However, the actual ban was not of polysilicon but of metallurgical-grade silicon, a precursor for polysilicon. This was problematic for the industry because tracing the supply chain back that far is difficult.

The material is so many steps removed from completed panels that just about any module coming to the U.S. can’t yet prove it doesn’t contain Hoshine material, Philip Shen, an analyst at Roth Capital Partners, said in a research note.

So, modules are being stopped at the border, and solar deployments to mitigate carbon are put at risk in an effort to punish China’s violations of the human right order. The implicit understanding of this kind of sanction is that if the costs imposed are great enough then the target country’s decision-making calculus changes and the violation might end. However, empirically sanctions—even ‘smart sanctions’—are as often found to have no effect or even strengthen rather than harm targets.

But here again the weird overlapping orders rear their heads. The Trump administration’s solar tariffs not on human rights grounds but as an example of China violating the trade order, presumably pushed by domestic manufacturers, the desire to target China to get the game of a trade war going that could be ‘resolved’ in order to serve as a campaign piece for re-election, and without any real consideration of the possible downside of slowing solar deployment as they thought little of the climate change problem.

The Biden administration has kept Trump’s tariffs in place and added additional limitations with a distinct justification despite having the opposite view on climate change. The divide within the US solar sector appears to be between those interested in manufacturing panels domestically and the numerically dominant installers. The Solar Energy Industries Association called for a repeal of the tariffs:

“There are no two ways about it. It is time to end the job-killing Section 201 solar tariffs. They are a multibillion dollar drag on industry growth. And leading domestic panel manufacturers are thriving, both here in America and globally. If we hope to reach our ambitious climate goals, we must accelerate solar deployment, not hinder it with unnecessarily punitive trade measures.

But Biden’s administration thinking is split here as well. Deployment of solar is great, deployment of domestically-manufactured panels made by union workers would be even better. While I do think that ramping up solar production is needed for resiliency, positive subsidies for US factories seems smarter than taxes and bans on imports.

Officially, Biden is using the trade order to punish Chinese actions on human rights in ways that threaten progress in the environmental domain. Chinese actions are as convoluted — if not more so (polysilicon production is centered in Xinjiang because of … cheap coal and labor; feed-in-tariffs have been pushed up and down; when solar and wind construction was subsidized, they were built and then left unused…).

I’ll end for now. These arguments connect to a paper that Christina Pan and Jessica Chen Weiss are writing that I’ll share once it’s ready. Stay safe and cool, everyone. It’s a hot mess out there.

“I have suggested that there is often a high degree of contestation within and across orders. One would therefore also have to code each order on its degree of coherence or contestation, and weight the aggregation of compliance with norms and institutions within an order by the degree of contestation of that order” (p. 58)

Interestingly, Nemet’s most cited article “Beyond the learning curve: factors influencing cost reductions in photovoltaics” is from 2006, pre-dating China’s emergence as a driving force for price declines and supply expansion.