Happy new year, which is to say that I am grateful that you and I both completed another trip around the sun on this ocean planet of ours as delineated in the traditional manner (assuming one treats papal bulls from the late 16th century as traditional at this point).

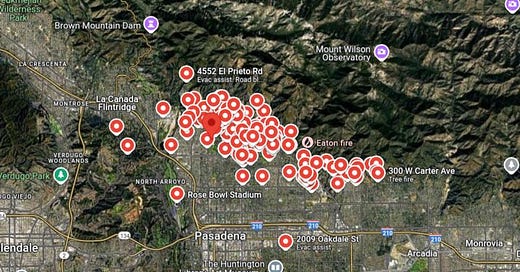

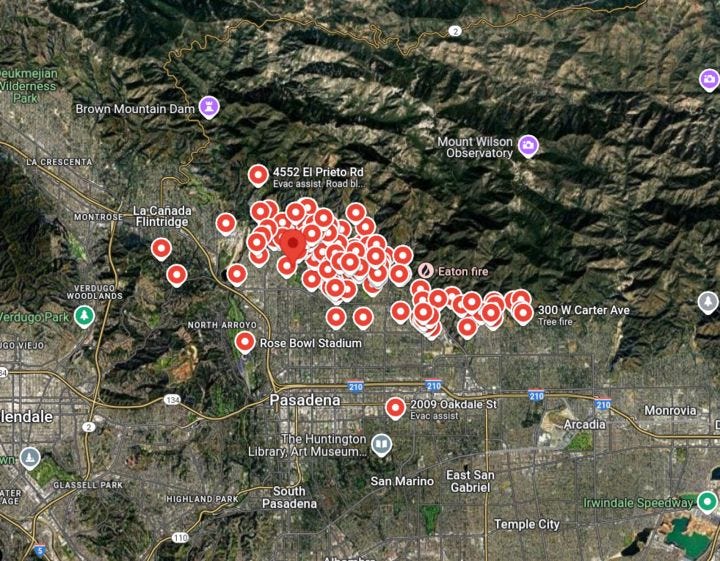

This post was half-drafted before fires began devastating northern neighborhoods of Los Angeles (Pacific Palisades, Pasadena, Altadena, etc). You can and should read about what is happening there, here’s the LAT and the NYT. These are climate-induced emergencies, and people in areas of danger, especially those under mandatory evacuation orders, need to flee to safer ground. The Pacific Palisades fire began yesterday afternoon (Jan. 7), while the Eaton Fire started later in the evening but is raging and sending embers into truly urban parts of Los Angeles.

I mention these fires not just because they are happening now. They are a climate-induced disaster of the utmost seriousness in a city I deeply enjoy affecting people I love and millions more and will likely represent the kind of financial losses that will further our insurance apocalypse spiral where actuaries end up dictating policy rather than elected politicians. As such they connect directly and deeply to the subject that I was writing about in this post.

While 2025 remains a number that feels deeply of dystopian sci-fi novels, here we are. I’ll lay out my plans for the year in another post, but first need to plug a piece that at some level I’ve been working on for three years (yikes).

Back then there was a bit of a ruckus on ye olde Twitter about an article published in the American Political Science Review titled ““Political Legitimacy, Authoritarianism, and Climate Change.” I posted about the arguments and controversy in what remains one of the favorite pieces I’ve written. Here’s how I began:

A recent political science article claimed that if democracy fails to adequately respond to the climate crisis, then ‘political legitimacy may require adopting a more authoritarian approach.’ A furor ensued—eco-fascism, Fox News, and more—that muddied the waters instead of clarifying them. Academics need to do more to engage in the climate debate, and to do so thoughtfully, both in journals and in public. The nature of digital debate often makes that difficult, with more views accruing to wilder claims, but responsible scholarship requires slowing down the debate and resisting the lure of internet sensationalism. The climate crisis is a global phenomenon that is unfolding now and will continue to do so over the course of many human lifetimes. That scale makes it thornily resistant to simple narratives of cause and effect.

Go read the whole thing, as they say.

My friend Gabriel Rosenberg published it over at his substack, which helped it reach a much bigger audience than if I’d posted it here. But while there is something exhilarating about the speed with which posting can happen and inject ideas into the discourse, in the end, I was trying to dispute the claims of an academic article and that such debates should also take place in our journals if those journals have any connection left to their original purpose (rather than just being venues for quantitative metrics of performance to be collected for subsequent assessments to be offered). And then the waiting begins. To be fair to myself, I published a book in 2022 and then moved in 2024 and haven’t exactly been sitting on my laurels in the interim though I will admit to posting a lot. And just over a year ago, I was posting on Bluesky about this project when someone I was citing noticed and we got to scheming up a collaboration.

The end result is now published at the Journal of Democracy as “Resisting the Authoritarian Temptation,” (our preferred title is now being used for this post), and I think it’s a banger. Here’s how it starts:

The unprecedented "natural" disasters of the climate age challenge not only individual and community resilience, but institutional resilience too. Governments have been slow to respond to climate change, slow to prevent further damage to our atmosphere, and slow to prepare for what is coming. Democratic governments, it is sometimes said, are worst of all at these tasks. Integrating the immediate economic, social, and political realities of energy production and consumption with complex, science-driven imperatives is a difficult if not impossible challenge, and governments based on wide discussion and free consent are said to be unsuited to it. Indeed, the failures of democracies and democratic institutions in meeting climate challenges have led some scholars and activists to question whether democracy is functional at all in this new world. Some even publicly support authoritarian responses—perhaps temporary, perhaps not—to the climate crisis.

This support is misguided. Democracy in fact possesses unique resources that make it better, not worse, than authoritarianism at dealing with emergencies and crises. Calls for antidemocratic solutions to climate-related problems should be resisted. Energy's centrality to the climate problem does make for genuine challenges in democratic contexts, but authoritarianism is not the answer. Yet both theory and practice have accustomed us to expect that crises and greater concentrations of power will go hand-in-hand, which may help to explain why authoritarianism appears attractive to some.

Nevertheless, calls for eco-authoritarianism rely on empirical, conceptual, and normative confusions: Claims that authoritarian systems are better at handling climate problems are flawed. They ignore empirical evidence and overrate authoritarianism while underrating democracy. The special resources that democracies and only democracies can bring to bear in the matter of climate change deserve to be spelled out, and the greater (not reduced) salience that democracy's specific strengths assume in times of crisis and emergency deserves to be more widely appreciated. As we face the road ahead, democracy remains essential. Trading away self-government for the false promise of authoritarian superiority would be a grave mistake.

The piece in particular dives into the idea of the “climate emergency.” We argue that care should be taken with such language, that “climate emergency” should be reserved for actual climate-induced emergencies like the fires burning LA rather than tossed about as a sign that whatever township or civic organization takes the climate challenge seriously.

That frustration with the sloppy use of climate emergency also connects back to Mittiga’s argumentation, which he continues to defend. Indeed, the Journal of Democracy published our piece as part of a forum with commenters, including Mittiga, Thea Riofrancos, Lisa Ellis, and Emilie M. Hafner-Burton, Matto Mildenberger, Michael Ross, and Christina J. Schneider, as well as our reply, and so you can see a range of views and reactions to our argumentation.

There’s a lot going on in this discussion, but I want take this opportunity to dive a bit more into a few of the debates.

First, Thea Riofrancos penned an eloquent essay that gets past the name-calling to land on a harder question: how should we think about China’s relative success in its energy transition and in particular how can we learn from some of its political-economic features that seem to be key to that success while maintaining democracy? Her essay concludes on these points:

Institutionalized features of the political-economic system also played a major role: high levels of administrative capacity (including enforcement), iterative policy improvisation, fierce interfirm competition, and multidirectional communication between levels of government.8 None of these make China a democracy—on the contrary, the system is increasingly autocratic. But all mark deviations from the typical autocratic portrait of rigid, top-down policymaking, insulated and self-serving elites, and, especially, "decisionist" finality.

From my perspective, the key question for climate social scientists and theorists is how the institutional features noted above could be adapted for democratic contexts. For example, long-term economic planning has played a key role in China's green achievements. This planning requires administrative capacities that many governments lack, including empirically grounded forecasting of near-future trends and credible commitments to binding decisions. Ironically, given the Cold War ideological legacy that sharply opposes planning and markets, in China such planning has generated the political certainty that enables market signals to function, resulting in famously cutthroat domestic competition in the solar and EV sectors.

Although there is no inherent incompatibility between planning and democracy—and indeed, democratizing the economy while also confronting climate change would likely involve something like planning9—there are surely tensions between planning and electoral turnover. How can governments demonstrate credible commitments to economic plans when a functional democracy entails "bounded uncertainty"10 about which parties and politicians will be in office in the future? For this reason, building popular support for energy-transition policies is essential: Key to their durability is their popularity among voters, which in turn hinges on ordinary people seeing concrete improvements in their daily lives. This fact turns the multiplex temporality of democracy on its head. Collective self-rule is surely open-ended and iterative, which aligns well with the uncertainty (tipping points and threshold effects) and longue durée features of climate change.

However, in order to sustain public support for rapid, holistic climate action while also creating and consolidating political constituencies that demand faster and more comprehensive projects, benefits need to occur in the here and now. This is especially the case in the challenging context of a highly salient cost-of-living crisis and resurgent, ever more violent right-wing political forces. To save the planet, we do need to defend democracy—but that means a new approach to climate politics that connects planetary well-being to material improvements in everyday life, and does so through the sinews of grassroots social organization, electoral and legislative campaigns, and positive policy-feedback loops. This is no small task, but it is the fundamental task of this decade.

Yes. Those who point at China’s successes and imagine that Xi Jinping is making all of the right decisions about climate, which are implemented precisely to his will, and then wouldn’t it be great if instead of dealing with the messiness of democracy with people and their weird ideas about parking and heating their homes we could just have a good green dictator to do exactly the policies that match my preferences and aesthetics?

Those people are not understanding the complexities of politics in China or anywhere else. The description that Riofrancos offers here could be elongated a bit — Chinese solar investments arose in large part because of entrepreneurs seeing opportunities in German and Spanish subsidies, which came out of policies from elected governments — but the general question stands. How can we maintain policy stability in the energy transition with electoral turnover? For instance, Trump yesterday said that he wants “no new windmills” while he’s in office, and it’s hard to square that orientation with a commitment to clean electrification consistent with decarbonization. And yes, of course, in this specific case, those wind farms are paying taxes overwhelmingly in rural areas of red states, and so if companies in those states want more of them, I’d doubt that Trump or his appointees would stand in their way. But again the overall conundrum remains.

There is an institution at the core of economic governance in many democratic (and non-democratic) societies that operates with some independence from electoral turnover already: central banks. Perhaps if a similar technocratic energy policy maker could be put into place, then at least a subset of issues could be ruled out of bounds for the normal partisan knife fighting.

On the other hand, one could argue the opposite — rather than having too much democracy in our energy governance, we have too little. Those supporting this line probably focus on the capture of public utility commissions by the utilities and their allies. If ratepayers and other citizens paid more attention to these bodies (as Charles Hua of PowerLines is trying to foster), then perhaps the policymaking would improve and push towards solutions that accord with clean electrification for the future.

Others looking at the failures of utilities have pushed for marketization in the areas of the electrical system where competition seems plausible, yet as Brett Christophers’ wrote in his excellent book, The Price Is Wrong: Why Capitalism Won't Save the Planet, the profits that renewables generate under truly marketized conditions are insufficient to attract adequate investment to clean the power sector. And while I have some issues with the book’s analysis especially as related to the significance of storage, as I wrote in my review, it seems clear that state intervention to pursue society’s interests in decarbonized energy system is going to be necessary. Surely it is better to have communities and elected officials making decisions about where investments should be made and not fall back on (what is becoming the default of) having insurance companies essentially dictate policies about who can live where as they pursue their profits.

Second, the Californians (Hafner-Burton et al) critique us for not laying more blame at the fossil fuel companies. I agree that they are climate villains of the highest order, but as Lazar and I note in our reply:

In many political narratives, a strongman defeats the shady elite who have been thwarting the true will of the people. Such stories work because they resemble the truth or some degree of it. Emilie Hafner-Burton, Matto Mildenberger, Michael Ross, and Christina Schneider correctly point out in their response that entrenched fossil interests have the power to disrupt and delay climate action. (Indeed, outside one of our offices stand billboards trumpeting fossil fuel's role in keeping food prices low.) As our aim was to surface other sources of political complexity, we acknowledged but did not center this in our essay. We aimed to underline that fossil fuel–funded propaganda and political capture cannot be the whole explanation: Citizens' lives are deeply dependent on fossil fuels. Moving to a clean, abundant future means acknowledging that this complexity matters to citizens. Taking them as reasoning interlocutors with genuine concerns is as necessary as more-aggressive fossil-fuel regulation in the politics of a successful green transition.

No doubt the fossil-fuel industry is a major barrier and, in our view, must face the kinds of regulatory controls we have imposed on tobacco companies [ed note: OR MORE!]. But it is not the fossil-fuel industry alone holding back climate action that the majority otherwise supports. Even if it were the primary stumbling block, could we count on an eco-authoritarian to thwart the industry? As Hafner-Burton and her coauthors wisely observe, empirically, dictatorships—much more than democracies—favor fossil-fuel interests, which in return perpetuate dictatorships. The political logic underlying this is straightforward.

Maybe casting the fossil-fuel industry as the key villain in the climate drama is strategic in persuading the demos to act. But anyone who would harness this rhetoric should nonetheless engage the broader public's wide-ranging views and interests. The diversity of engagements between Canada's indigenous communities and the fossil-fuel industry provides a case in point.

There’s so much more to say on this other threads in this conversation. While I’ve been writing the Eaton Fire has spread and now has incinerated over 10,000 acres on the edges of and into the great metro area of Los Angeles. Climate change is a global crisis that sparks particular emergencies. Our failure to act is inflicting pain today, has already destroyed communities and ravaged whole countries. We need to act, but we need to do so in ways that will persist, sustainably, and that in my mind requires democracy.