Climate change is a hard problem, but contra Francis Fukuyama, we’re not cooked yet. The ubiquitous burning that powers and moves our society is invisibly warming the planet and building long-term risks, but it is also poisoning us all today with every breath we take. But air pollution’s very proximity provides an opportunity to move beyond doomscrolling and eco-anxiety, a chance to localize struggles and provoke action in the here and now that will improve human health and slow climate change.

Tell me if you’ve heard this one. Two frogs relaxing under some leaves on the edge of a pond on a mostly cloudy day are suddenly grabbed by a hungry chef and shoved in a leather sack. The chef boils some water and tosses one in, but it promptly hops out of the scalding pot and hides under the cabinets. Surprised, the chef rethinks his process. He starts another pot, puts the frog in and only gently ramps up the heat. This second frog, somehow unconcerned about the evident dangers of this situation and unaware of the near murder of his colleague, relaxes as the water slowly warms from tepid to cozy to toasty before dying as it comes to a boil.

This tale is used as a metaphor for global warming. Humanity, it asserts, would of course rescue itself if climatic changes were abrupt, but we are like the unfortunate second frog as the incrementalism of the crisis makes it possible to ignore until it is too late.

Now, it turns out that frogs do not stay in pots that slowly warm up. In fact, I’m a bit concerned that even this rendition of the myth will catch the eye of the great James Fallows who back in 2006 was already furious about its persistence.

Also, in a tragic twist, there’s little chance the first frog would survive any time at all in the boiling water.

So why do we turn to this myth? The most common cliché we have for this kind of argumentation — that subtle changes are easy to miss or dismiss — is the icy metaphor of the slippery slope. But this doesn’t work for global warming, and not just because ice is cold. There’s the ignorance (and perhaps innocence) of the frog as well. The frog doesn’t realize that it’s being cooked — and, in the analogy, we don’t either — except we’re the ones doing the cooking with all of our driving and flying and smelting and computing and refining and mowing and burning and, even, yes, cooking.

Just like the real frog, the signs of discomfort from a changed environment surround us. Incessant forest fires, rising sea levels, deeper droughts, more powerful storms, flowers coming up earlier and earlier, etc. As global temperatures rise, more and more people are succumbing to the heat.1

When heat waves come, they can be incredible deadly.2 On Thursday, July 13, 1995, Chicagoans faced temperatures of 106F, which with humidity felt like 125. For the next 10 days, the sweltering heat continued. Over 800 people were killed in the heat wave. Last year, the Pacific Northwest was hit by a record obliterating heat wave.

Like in Chicago, the sustained spike in temperatures killed hundreds of people.

For a heart stopping description of what death by heat stroke feels like read this.

Your head is pounding, your muscles are cramping, and your heart is racing. Then you get dizzy and the vomiting starts. Heatstroke kills thousands of people every year. This is what it feels like—and how to know when you’re in danger.

But the Pacific Northwest if famously temperate, at least in normal times. And so cranking up the heat there, even to an absurd extent like happened last summer, will be terrible but not calamitous. If a heat dome of similar intensity to what hit the Pacific Northwest was placed in the right location at the right time and extended for a full week like the Chicago heatwave of 1995, then a world-changing disaster could ensue.

The Ministry for the Future’s Optimism

This kind of event is precisely how Kim Stanley Robinson begins his recent sci-fi novel The Ministry for the Future. In 2025, twenty million are killed in apocalyptic fashion in northern India, as a heat dome stuck up against the Himalayas knocks out the electricity grid which powered the air conditioning which provided the last chance to keep people cool from the incessant heat and humidity. This epochal event drives the action of the novel, with first a complete social revolution in India, which embarks on using aircraft to release sulfates to block sunlight on the order of the 1991 Mt. Pinatubo eruption (“Or a double Pinatubo, yes.”). An eco-terrorist organization, the Children of Kali, operates on the edges of the text, its relative causal power unclear amidst the official global actions coordinated by the novel’s principal protagonist, Mary Murphy, and the UN-based Ministry for the Future that she leads. A whirlwind follows. Carbon coins to pay owners of fossil assets to keep them in the ground, the wholesale grounding of jets after a sufficient number are brought down through drone strikes, and a particularly clever elimination of beef from global diets through wholesale infection with mad cow disease. The efforts and more are wildly successful; by the end of the novel, CO2 levels are dropping rapidly (from 475 to 454 in just four years). Currently, we’re at around 420 and adding over 2ppm a year; the environmental organization 350.org seeks a return to that “safe concentration of carbon dioxide.”

The Ministry for the Future already has been reviewed and discussed extensively, including in a Crooked Timber seminar, what I’ve long considered a premier compliment for ambitious books.3 And while as a novel, it is far from perfect, its opening grabbed a hold of the zeitgeist and got many to contemplate the deadly seriousness of climate change and forced them to reconsider their political priorities anew.

But I’m here instead to respond to a more recent and critical review from a prominent source. If books can be published with the title the End of the End of History, then the prolific and prominent public intellectual Francis Fukuyama needs no introduction. His review of Ministry has the plaintive title: We’re Cooked.

I suppose that this novel is intended to be a hopeful blueprint for a way out of the climate crisis. Knowing what I do about global politics and human nature, however, The Ministry for the Future left me rather despairing that it will ever be solved. For all of his seeming political sophistication, Robinson posits the most optimistic possible political developments at every turn, developments that enable Russia, China, the United States, Europe, and the developing world to work together cooperatively to solve the problem.

To be fair to Fukuyama, my initial notes after I finished the novel were quite similar:

Eco-terrorism off-screen. Lots of refugees. Avoids a lot of difficulties—right-wing reactionaries, NIMBY-types, etc. for a book that begins with 20 million dead, it is incredibly optimistic about where we would end up—literally reversing CO2 levels downward by 20 points in a few years.

Fukuyama, though, goes even further, wondering if the implausibility of some of the actions in the novel suggested something darker:

All of these outcomes are so ludicrously unrealistic that I am led to suspect the author’s intention is rather different. Is he really trying to show that we cannot possibly get to seriously effective climate policies without resorting to violence and authoritarian practices? Robinson has the strange view that central bankers actually run the world, entirely detached from the societies that appoint and empower them. So it is sufficient to convince a group of perhaps a dozen people to do the right thing, and the crisis will be essentially solved. It is true that central banks are the least democratically accountable of modern institutions, so perhaps he is pointing beyond democracy. This can only happen because, in his book, populations around the world complain a bit, but ultimately acquiesce to the sacrifices and disruptions brought on by a tiny group of technocrats.

Now, the most recent issue of this newsletter was about a long piece on authoritarianism and climate change. I did not spend a lot of time there on the legitimacy issues of the delegation of authority to a set of technocrats by democratically elected officials. Is it so strange to think that “central bankers actually run the world?” Sure, Jerome Powell can’t just declare himself God Emperor but actually tinkering with central bank independence (rather than just tweeting about it a la Trump) might entail costs. I’m still grappling with how to think about technocracy and climate change, which will be the subject of a future post (or several). If you can’t wait, you can read my paper on The COVID Crisis, Expertise, and the Future of Legitimation and draw your own inferences.

How Wicked Is Climate Change?

Rather than debate the level of optimism of a cli-fi novel, I want to interrogate the idea that climate change is the ultimate political wicked problem. When I have taught this idea, here’s what I’ve said:

Climate change as a “wicked problem.”

a definition is elusive and a definitive solution is lacking.

inherently societal problems that may have a technical component

many stakeholders, and any attempt at a solution will have multiple consequences as its implications ripple across the affected parties.

inherent complexities and uncertainties in underlying issues, particularly as they related to economic, social, ecological, and geopolitical factors.

In a journal article from 2012, Kelly Levin and co-authors go one step further, naming climate change as a “super wicked problem”

Super wicked problems comprise four key features: time is running out; those who cause the problem also seek to provide a solution; the central authority needed to address them is weak or non-existent; and irrational discounting occurs that pushes responses into the future. Together these features create a tragedy because our governance institutions, and the policies they generate (or fail to generate), largely respond to short-term time horizons even when the catastrophic implications of doing so are far greater than any real or perceived benefits of inaction. How do we reorient our institutions and policies to respond to our long-term collective interests so that this tragedy can be overcome?

No one has yet had the courage to stake out the position that climate change is actually a super duper wicked problem.

Thinking of climate change as too much for our politics to handle is ubiquitous. For instance, Foreign Policy ran a piece last month with the unfortunate title “What if Democracy and Climate Mitigation Are Incompatible?” that falls into many of the same traps that I discussed last time in focusing on the flawed responses to the climate emergency of real-life existing democracies rather than the fact that they’ve done a better job than dictatorships so far. But beyond pining for an authoritarian to solve the problem, its conception of climate change as too big, too much, and too invisible to galvanize action is common.

Climate change, in economic terms, is a commons management issue. The goal is to create a stable ecosystem, but every country has an incentive to free ride and let others swallow the costs of providing it. It’s in nobody’s immediate self-interest to go first and bear the costs of mitigating carbon emissions: Why commit to something if others won’t? That’s especially so since early movers on climate policy only earn a small share of the global benefits while paying a disproportionate share of the costs.

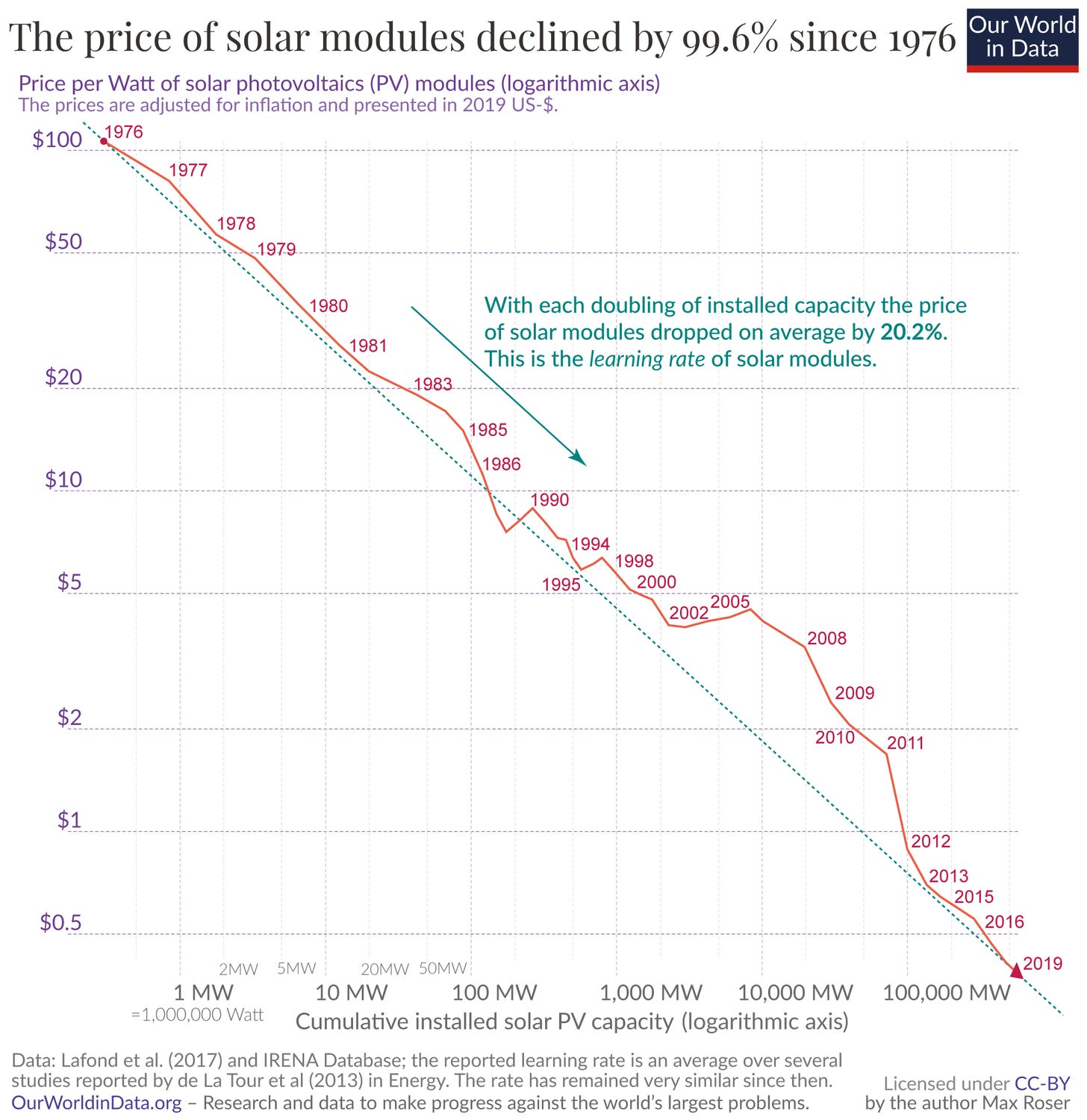

This just isn’t it at all. This kind of “free-riding” argument made much more sense twenty years ago when solar prices were 20x what they are today. Renewables today are providing the cheapest electricity ever.

The United States, Japan, Germany, Australia, and China have all already paid the upfront costs to make mitigation affordable.4 The core political problem of global warming is not free riding but navigating an energy transition.5 Companies and people have trillions of dollars in assets that were built for a fossil-based economy, and everyone has to figure out where to put all of the solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, and power lines needed to decarbonize.6

My first post here analyzed an excellent paper written by Jeff Colgan, Jessica Green, and Thomas Hale, Asset Revaluation and the Existential Politics of Climate Change, that tries to break the mental frame of the collective action problem. This is not to deny that there are forces for delay (and even some still in denial about the problem at all)7, and claims that it will be too expensive to persist. Many would prefer some other town to have to deal with having wind turbines nearby or cutting down their local forest to put in a solar farm. The costs of change feel localized, but all too often, the benefits of going green feel diffuse. And the belief that benefits are diffuse makes commentators and politicians think they are not real or worth fighting for because there won’t be the symbols of success to point to and claim credit for that politicians crave.

But far from being distant, the benefits are right in front of us, and even more than that, inside us.

Seeing Through the Smoke

David Wallace-Wells had an explosive success with The Uninhabitable Earth. The book began as NY Magazine’s most read story ever in 2017, which attempted to imagine the horrors of a world with 8°C of warming. While some, like climate scientist Michael Mann, expressed frustration at the “doom” and criticized it as likely to provoke paralysis (which we’ll get to shortly), Wallace-Wells has continued to produce some of the most interesting journalism on climate change for NYMag. But in my estimation, the piece most likely to change the politics of climate change was published by the London Review of Books: Ten Million a Year.

I have a friend who saw something horrific and described it in such memorable fashion that I have trouble getting the image of this single death out of my head (feel free to skip the rest of this paragraph if you’d like to not be so scarred). In Beijing, on what I imagine was a chaotic and busy road, a bus ran over a man and squished his head like a grape. This kind of visceral description worms its way inside of our brains and remains there, as a warning about a potential danger that could befall us.

Individual traumas strike at our core; for a thousand generations humans and our ancestors have been scared of being crushed by a heavy object or eaten by a predator or falling a great distance or drowning in murky water.

Our brains have not been habituated to think about the mortality effects of chronic exposure to particulates in the air. And yet, we know that around 10 million lives are lost each and every year to air pollution.

Particulates far too small to see are breathed in and end up all over our bodies. Their ubiquity finds them in the brainstems of babies and even in the womb.

Many books have been written recently about this scourge: e.g., Beth Gardiner’s Choked: The Age of Air Pollution and the Fight for a Cleaner Future, Tim Smedley’s Clearing the Air: The Beginning and the End of Air Pollution, Gary Fuller’s The Invisible Killer: The Rising Global Threat of Air Pollution – and How We Can Fight Back, and Ma Jun’s The Economics of Air Pollution in China: Achieving Better and Cleaner Growth. We are familiar with the idea that breathing in polluted Beijing or Delhi is akin to “smoking multiple packs of cigarettes a day,” and that smoking kills despite big tobacco’s years of anti-health propaganda. Yet the obvious implication — that dirty air isn’t just making the sky turn gray and giving everyone coughing fits but actually killing people — somehow escapes our ape brains. Sometimes governments have tried to make these statistics disappear, like in 2007 when a World Bank study on pollution deaths in China was suppressed.

These deaths from crud in the air — burning fossil fuels, forests, chemicals, etc — are of a scale that is difficult to fathom. Ten million a year, one hundred million a decade. Outside of a heat wave straight out of science fiction, few other impacts from climate change are as likely to kill so many so quickly. And it’s already happening now.

Bill McKibben wrote Eaarth out of a frustration that everyone talked about climate change as a problem for the future — “our grandchildren” — when it had already turned our world into something so different that it deserved a new name. That book was published a dozen years ago.

But do not read this as doomism, as another disaster in a series of disasters that make up the polycrisis of the anthropocene. This pervasive dying from urban air pollution is something not only that we can tackle, but something that we have tackled successfully before many times.

We Can Do This; We Have Done This

In 1935, Charles Bolduan of the New York City Department of Health was proud enough of the work the city had done to boast of its “conquest of pestilence.” In fact, he worried that this success might “make us too complacent, and inclined to believe there is little left for health officers to do.” In particular, sanitation and clean water kept the scourge of cholera from killing New Yorkers dramatically lowering death levels from their 19th century highs.

It would take longer to realize how deadly air pollution was.

Like how we forget that city streets used to be full of horse manure, we forget how smoky city life was a century ago. If you left a paper on a bench and came back to it after an hour, you might need to wipe it off to be able to make out the text. After a full century of being derided as a smoky city, Pittsburgh finally implemented a smoke control ordinance in 1946 following the success of St. Louis’s policy.

When they finally put it into place, the change was dramatic.

The 1952 London Smog was said to have killed 12,000. But, after disaster and in response to popular pressure, pollution in these cities was reduced through government action.

China’s cities became famous for their poor air quality. In April 2008, the US Embassy in Beijing began collecting samples of PM2.5 (particulate matter under 2.5 micrometers in diameter) in the city’s air, and in July it started tweeting the results hourly, @BeijingAir, despite complaints from Chinese authorities. In October 2010, the account tweeted that Beijing’s air was “crazy bad” as its reading exceeded 500—twenty times the World Health Organization’s guideline—after programmers had jokingly coded in that label for absurdly high scores that fell beyond the index, not expecting it to ever be triggered.

The following year, Beijing’s air quality was again, by international standards, dangerous. As it had the previous fall, the US Embassy’s monitoring equipment registered scores so polluted that they were “beyond index,” while the Beijing city government officially reported that the air was merely “slightly polluted.” Yet this episode cut a deeper impression. Pan Shiyi, a noted real estate developer, sent multiple messages to his over sixteen million followers on Sina Weibo in early November 2011, calling for the Chinese government to monitor PM2.5 rather than just PM10 (larger particles). Pan’s Weibo post included a poll; over 90% of 40,000 respondents agreed with his recommendation. Just a few days later, Premier Wen Jiabao acceded to these requests, saying that the government needed to improve its environmental monitoring and bring its results closer to people’s perceptions. New standards on air pollution further restricting sulfur dioxide and nitrous oxides and adding PM2.5 were put into place in February 2012. Hundreds of stations regularly releasing air quality to the public were established across dozens of cities by the end of that year. PM2.5 is now incorporated into a broader air quality index (AQI) featured in weather reports on state media and available on phones through a variety of apps. Shortly thereafter, Wen’s successor, Premier Li Keqiang declared a “war on pollution,” and air quality has improved dramatically in the half-decade since. Popular pressure about a countable, observable phenomenon like urban air pollution worked, even under authoritarianism in China.

London cleaned its air, so did Pittsburgh, and Chicago, and Los Angeles. Mexico City has come a long way, as have most Chinese cities. These leaps can be replicated in Delhi and Cairo and other cities around the world. Basic regulations can make a lot of difference, and clean technologies powered by renewables make the case and the job easier.

These kinds of improvements obviously translate into better health and higher quality of life for those spending time in the cities. However, the job is not done. The more we study air pollution, the more we realize the damage it does to our bodies. A new study emphasized that even in a country with relatively clean air compared to historical standards—the contemporary US—pollutants were killing people en masse. As the NYT wrote:

Researchers at the Health Effects Institute, a group that is funded by the Environmental Protection Agency as well as automakers and fossil fuel companies, examined health data from 68.5 million Medicare recipients across the United States. They found that if the federal rules for allowable levels of fine soot had been slightly lower, as many as 143,000 deaths could have been prevented over the course of a decade.

Air in American cities in the past decade has rarely been described as sooty, with the important exception of when they are blackened by smoke from forest fires, and yet even the seemingly clean air surrounding them contributes to early deaths.

We also spend a lot of time inside our homes, but as hopefully we’ve come to understand with the COVID-19 pandemic, the indoors isn’t always a refuge. In fact, another recent study emphasized that your gas stove just might be trying to kill you.

The appliances release far more of the potent planet-warming gas methane than the Environmental Protection Agency estimates, Stanford University scientists found in a study published Thursday in the journal Environmental Science and Technology. The appliances also emit significant amounts of nitrogen dioxide, a pollutant that can trigger asthma and other respiratory conditions.

This viral tweet thread highlights the same issue, and despite being initially skeptical of the importance of gas stoves — which are a tiny fraction of US emissions — he comes around to think that he needs to probably ditch his gas stove.

Every study that I’m aware of points in the same direction: we should do everything we can to stop burning things because the fumes are killing us and cooking the planet.

Immediacy, Action, and Climate Anxiety

The implication for climate politics then is that action doesn’t need to be justified by harms that feel distant to us — to nebulously defined ‘nature’ or to people living far away from us or to generations yet to be born. Obviously all of those things do matter, but they are easy to discount in today’s economic models and political considerations. What we need to focus on is that climate change is here and now. Electrifying buses is not just about reducing carbon dioxide emissions warming the planet but about improving the health and academic performance of kids. Using induction stoves cuts down on methane and NOx that we breathe while watching movies, tucking in our children, playing wordle, or sleeping. Moving away from fossil fuels is the way to save our bodies and save the world.

It also suggests a way to maybe save our minds. The NYT published multiple stories about how climate change is messing with our brains this past weekend, which I believe officially makes it a trend. The first describes climate anxiety and specialized therapy as a tool to combat it. In the second, the always sharp Amanda Hess points to a specific form of doomscrolling, which focuses on climate:

The casual doomsaying of social media is so seductive: It helps us signal that we care about big problems even as we chase distractions, and it gives us a silly little tone for voicing our despair.

Most of all, it displaces us in time. We are always mentally skipping between a nostalgic landscape, where we have plenty of energy to waste on the internet, and an apocalyptic one, where it’s too late to do anything. It’s the center, where we live, that we can’t bear to envision. After all, denial is the first stage of grief.

Watching Finding Nemo with my twins for the first time a couple of weeks back did lead me to wonder if there’s any chance that they’ll get to see the Great Barrier Reef in person before it is bleached to lifelessness. And there are more than enough stories, reports, and studies to overwhelm anyone with downbeat news. But it’s important to remember that climate change is not a cliff nor a comet coming to destroy us. After all, it’s already here. But also every 0.1 degree of warming that we keep from happening makes a difference. And so activism at the local level can improve our lives and our sense of efficacy; politics is for power, after all. For instance, the US’s largest grid operator, PJM Interconnection, has suggested a two year delay on new connections as its overwhelmed with new solar projects. Its slide deck describing how to reform operating procedures to deal with the growing queue only brings up adding more staff on slide 15 in “other opportunities to explore.” Maybe you think we should try to bring solar plants online faster than that. You could contact your Public Utility Commission and see if they could maybe work on that.

Climate change is a reality that is harder to deny than ever before. And straight denial has ceased to be the main problem. It’s here in our lives, in weirdly warm February days, in heatwaves that kill, in fires that devour sequoias that have lived for two thousand years, but also in our lungs, our blood, and our brains. It’s killing us, stealing years from our parents, our friends, and our children.

Addressing the emergency means confronting difficult questions, not just fighting for conservation but also for construction. It’s the harder political work of changing our infrastructure, building out new facilities, growing supply chains, mining resources, and more all while attempting to do that in equitable fashion on a polluted planet with a changing climate. But the political challenge of addressing climate change at least does not have to be compounded by distance over space and time. The costs are already present here and now, in unforgettable events that scar us as individuals and our communities, but also in the very air of each breath we take.

Beyond well known dangers like dehydration, people chronically exposed to hot, humid conditions have been known to suffer from arguably related issues, like kidney disorders. For instance, the New England Journal of Medicine described a Chronic Kidney Disease of unknown origin (CKDu) as a “sentinel disease in the era of climate change” which is the second leading cause of death in Nicaragua. Although debates exist about the extent to which climate change can be blamed.

As of today, far more people die of cold than of heat globally is evidence of the persistence of poverty. Trends indicate that global temperature increases are shifting this burden.

I’d particularly recommend Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò’s contribution on the way the novel considers the possibility for transformative politics in the Global South versus Global North.

For more here, see Gregory Nemet’s work on How Solar Got Cheap. Bentley Allan, Joanna I. Lewis, and Thomas Oatley edited a special issue of Global Environmental Politics all about the rise of green industrial policy.

Setting aside agriculture for now.

This, for instance, I find infuriating.

Although apparently I need to catch up on all of the Andreas Malm reading as Thea Riofrancos recently posted this surprising claim: