This is a post about time, profits, expectations, and motors of history. It’s about Keynes, the United Arab Emirates, China, and Adam Tooze. The tl;dr is that people live in a multiplicity of structures but do so diversely. The strength of particular dynamics and structures — the strongest ones could perhaps be called hegemonic — can wax and wane but are never dispositive in and of themselves as to the fate of individuals, projects, communities, leaders, or nations. Yet to ignore broader structures and fixate on the historical happenstances elides real connections, expected and unexpected, in ways that produce poor analysis. We should be catholic in our social science, open to synthesizers and particularists. But as we debate about the causal power and influence of different factors at key conjunctures, we should also remember that the world is burning. Holding too tightly to our sacred texts or demanding sophistication in analysis as a prerequisite of speech is anti-democratic. If we’re to take advantage of the opportunity afforded by the collective necessity of transforming human energy systems to invigorate and improve the ways we govern ourselves and this planet, then let’s do that and not pre-grieve our inevitable failure.

Profits and Prophets

Vertical videos, algorithmically selected and dispensed on our phones as we crane our necks to stare at the little black mirror in our hands, absorb a disquietingly large percentage of human attention in the year of our lord 2025. One clip that was pumped into my veins by the good GPUs over at Youtube is from the sketch comedy slash game show “Game Changer.” Contestants are given prompts and expected to uproariously fill the time. Here Brennan Lee Mulligan reacts to the following prompt: “Explaining the Rules to the Board Game ‘Capitalism’.”

So, number one, the first rule, and this is actually a really cool game design, is the games already started. You were actually born into it. The moment you were born they registered you with the game and what’s sort of fun about that is the people who made the game are always winning and will always stay winning. So, you are interacting with a world in which everything either has a monetary value or if it doesn’t have a monetary value, it is “worthless.” So the cool thing about that as a system is it’s like, oh man, I have this piece of property, and it’s like, cool, that is worth whatever you can get someone else to pay for it. It’s a fixed amount when you’re “poor,” but if you’re not poor — “poor” is a status condition you can have in the game which you all have….

It’s funny because there’s so much there that feels painfully true, but it merely scratches the surface of the oddities of the economic system we all find ourselves enmeshed in. Capitalism can feel like the real rules to life as a human on this planet.1 Yet Brett Christophers might argue that Brennan Lee Mulligan is making a very common mistake in his description of the game’s rules. In his great book, The Price Is Wrong (my review here), Christophers argues that focusing on the monetary value of everything — its price — is not the best place to start when thinking about “how the economic world actually works in practice.” Supply-side and demand-side economics are both “price-oriented theories” for Christophers, and both fail to root their analysis in political economy which “fundamentally turns not on price but on profit” (p. 136). Using Anwar Shaikh’s coinage of “profit-side” and quoting him that “both effective supply and demand are regulated, through different channels, by expected profitability,” he emphasizes that firms prioritize profits. This emphasis is at the core of Christophers’ book, which critiques the idea of levelized cost of electricity and specifically the radical drops in LCOE for wind and solar, as indicative of the economics of the energy transition having been won or become simple. Christophers went back and forth with Tooze and Kate Aronoff at an event back in October in a fascinating conversation.

I’ve already mainly said what I’d like to say about the book, but I do want to pry open the aperture of expectations and expected profitability. Because while there is a bankerly/consultant class version on investment that looks at a spreadsheet with a specific number for expected profits — based on some set of modelling data that those holders of money are using (hopefully with some kind of confidence interval). In this world of eyeshade wearing accountants, projects that have that number coming in below some hurdle rate or minimum acceptable rate of return will be nipped in the bud, and only those particularly profitable paths will be taken. This is obviously true. And yet there are all manner of people and companies that have made truly ridiculous investments and turned them into billions, and there are individuals and funds and even banks who will take bets. There are all kinds of critiques of models of expected profitability that one would name — demand is underestimated or costs are overestimated or quality will overcome the price difference of a cheaper competitor or open up a new market segment or something else. Entrepreneurs play the game and do so flush with animal spirits. Sometimes they fail, burning cash and buttressing the spreadsheets foresight, but sometimes they succeed and open the door a bit further for future investors to come with another piece of anecdata. The above are cases of not a dispute over the need for a particular rate of profit but over whether this project with this leader will be expected to earn that high rate of profit, to get over the hurdle.

But there are also other cases where a lower rate of profitability is just fine — infrastructure investors are often seen to be accepting of lower rates of return, usually accepting that tradeoff at least in part because of the stability of expectations around that low rate (something that renewables projects might fail at), but nonetheless it opens up the discussion to investors and financiers existing in economic activity with ranges of expected profitability. To be fair, Christophers acknowledges such possibilities (in the linked conversation more than in the book).

Why harp on such things? Because there are all manner of issues related to decarbonization where profitability is in question. Christophers emphasizes renewable generation and deployment — wind and solar farms — face all manner of difficulty in making money. Another notable one is one step earlier in the chain: the manufacturing of those renewable technologies. As I memed it awhile ago:

As everyone reading this knows, Chinese firms have come to dominate the solar manufacturing business and have done so by scaling up and up and up. We’re at an annual manufacturing capacity of 1.1 TW of panels, but the firms that have done so are now dealing with a glut of panels (too much supply relative to demand) and cutting prices in the hopes of getting some payback for their investments. Their profitability is in the toilet, as it were. In fact, this is so much of a problem that the Chinese government is trying to help the manufacturers come together to operate something of a cartel to manage the price and are explicitly referencing OPEC as a model.

To be a bit more concrete about what has happened here and why it gives me hope vis-a-vis Christophers account is that individuals and firms in China borrowed money and used retained earnings and any other money they could find and built massive facilities to manufacture polysilicon and ingots and wafers and cells and modules. They did so with the belief that they could do it better than their competitors and that solar was the future and that the demand would materialize at prices where they would earn adequate profits. Perhaps they thought that there would be tight moments where weaker firms would fail and their own profits might evaporate but that they would then return. Maybe some even foresaw that the Chinese government would step in, that their investments had made themselves of sufficient size that they were too big to fail. Or perhaps they believed that it wasn’t their scale that mattered — the employment numbers in solar manufacturing aren’t that large since it’s a highly automated and capital-intensive process — but that they helped provide security to the nation by allowing China to power its society with locally generated energy rather than remaining reliant on imported oil and gas. Or a dozen other possibilities that may or may not play out over the next period of time. And to be clear, some of these bets will go bad. Some firms will crash and have to sell out. But the animal spirits that led to such massive investments that the price of solar cratered in ways that make it possible to envision a decarbonized planet without having to immiserate the world have already altered the trajectory of history.

But this is just one of many different profitability challenges facing planetary decarbonization. I’m confident that we can make building in dense housing profitable and electric vehicle manufacturing and heat pumps and maybe improved home insulation. But how can we make it profitable to get people to reduce their beef consumption? To fly less frequently? To not ping a hyperscale data center for plagiarism assistance every damn minute of the day? To pull carbon from the air and bury it back underground in the caverns from which we excavated coal?

We need more imagination about how to move forward. Some of that will come from entrepreneurs — the clean tech startup space is fascinating: clean cement, clean steel, enhanced geothermal, virtual power plants, heat batteries, ebikes, clean finance, direct air capture, and more (including carbon offsets which let’s just not talk about). Some of it will come from policymakers and activists, whether it simply absorbs private risks and guarantees some profits or whether it manifests as a big green state. Management of capitalism isn’t new, political science has been writing about the varieties of capitalism for long enough that new literatures are emerging to try to invigorate discussions that had been abandoned as either already answered or unanswerable. Some movement will take place inside of the structure of relations that we call capitalism and others will be outside it or remake it or replace it altogether.

Keynes and Time

We, individually and collectively, make our own futures. Of course we face constraints in doing so, imposed on us by physics and chemistry and biology as much as by human structures that envelop us. Unlike the avian dinosaurs that nibble at the birdseed we feed them, I cannot flap my arms and take off into this planet’s blue sky. I also cannot call on my private jet to fly me someplace warm on a snow day because I do not own a private jet and do not have the money by which to acquire one. I also cannot single-handedly upgrade Amtrak to make reliable, electrified high-speed transit between DC and New York available tomorrow. But I can write white papers that advocate for good policies and share those of others as well. I can study and write about China’s decarbonization to help those arguing against using a caricature of it. Collectively, we can make markets for products we want to see, deliberate with our colleagues and friends about our preferences and priorities, and push politicians to act in ways we believe to best reflect our values.

The political theorist Stefan Eich has two pieces building off of Keynes that I want to highlight. First, he had a very nice essay on Keynes and time that came out at Tooze’s Chartbook. When you write a phrase that becomes as ubiquitous as “in the long run we are all dead,” you run the risk of having that quip devouring the context in which it arose and the broader thought of the individual that penned it. This is particularly unfortunate for Keynes, who if you know three or four things about him those might include that he wrote something called “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren.” He clearly cared about and reflected on the future. After all, the future is at the core of his economic insights, as Eich writes:

As he summarized in the preface to The General Theory (1936), “changing views about the future are capable of influencing the quantity of employment.” (xvi) Expectations thus have a profoundly reflexive, performative dimension that easily render them self-fulfilling or self-defeating, often tragically so.

If everyone believes that a recession is coming at t+1, then no on invests at time t which makes the recession happen and our expectations fulfilled. Usually we’re optimists and so booms predominate. Eich again, “Speculative visions of the future are thus performative in the sense that they feed back into how people act in the present.” But Eich shows how Keynes didn’t just think about this in business cycle terms. Yes the future is unknowable but

Facing up to uncertainty without giving up on betterment required modes of open experimentation that operated both on an individual and an institutional level. For Keynes, this entailed nothing less than cultivating new forms of collective life and social cooperation below the level of the state. “The true socialism of the future,” he declared in 1924, “will emerge, I think, from an endless variety of experiments directed towards discovering the respective appropriate spheres of the individual and of the social, and the terms of fruitful alliance between these sister instincts.” (CW 19, 222) As Keynes argued in “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” the pessimism of conservatives and reactionaries had to be rejected precisely because their conception of the fragility of economic and social life left little room of genuine institutional experimentation.

There is a genuine difficulty in imagining a future different than the one we live in. I’ll add that there’s something of a political difficulty beyond the cognitive one as well. Conceiving of better worlds, especially radically better worlds, can be dismissed as naive or not serious. I’m sure I’ve done it myself. My profession, academic identifying as a political science, is especially prone to cynicism. If economics is the dismal science, then political science is the cynical science.

For solid empirical reasons, political scientists dismiss the words of politicians as cheap talk and make base assumptions about their priorities — re-election, regime survival, etc. I’m not coming at political science (today), but I do think that this equation of sophistication with cynicism make imagining better futures more difficult. Dystopias sell better than utopias. It is perhaps safer to assume that the stranger could mean harm than to engage with him. It takes a kind of bravery to work past that and get to the human, to see no stranger at all. Because of course there are dangers and grifters and murderers and even some people that can tell fabulous stories about the emotional complexities of being human can also be, from time to time, sadistic and capable of violent sexual assault.

Even more directly on point is Eich’s article “Derisking as Worldmaking: Keynes, Climate, and the Politics of Financial Uncertainty” (apparently forthcoming at RIPE as part of a special issue that will be required reading). In it he argues for a “smart green state” as an alternative to the climate derisking vs. big green state fights of yore. But instead of just a middle ground that is smart (and who’s against smart? we might just get to that), he argues that a key piece of a truly smart green state is understanding radical uncertainty.

The article is not a policy paper and definitely not legislation with deep details figured out and to be argued but instead largely a reflection on the roles of risk and uncertainty in economics, international relations, and life. The article is rich, but take just this snippet:

But rather than reverting back to derisking or simply turning our back on policies that shape market expectations, this points instead toward the need for bolstering the democratic legitimacy of the Smart Green State, including the crucial role that more democratic central banks can play. After all, as I have argued, central banks engaged in derisking are already underwriting extensive forms of worldmaking, albeit of a hidden, conservative, and privatized kind.

We all remake the world by our thoughts and actions everyday, but some of us have massive levers through our control of cultural, political, and economic institutions that can allow for our worldmaking to dominate.

Mirages and Realities in Abu Dhabi

If you want to see a world that has been remade over the past five decades, you should probably go to China. But if you’ve seen that story already, then you could do far worse than to examine the United Arab Emirates.

I’m not going to touch on the international relations of the UAE and I hope at this point that you do not see me a simp for authoritarianism. It remains a monarchy with real restrictions on freedoms of speech and organization, and there are abuses that come with having non-nationals as 90% of the population as work visas are controlled by employers.

But it also has become a fascinating and wealthy country where 11 million people now reside and encapsulates the idea that possibilities can be taken and worlds can be remade.

Founded in 1971 following British withdrawal, there was oil but also a turbulent neighborhood with much larger powers (Iran and Saudi Arabia) and inevitably rivalrous city-states. I’m not going to do a capsule history here but just suggest further reading. What really distinguishes the UAE from the other Gulf states is that it has more successfully diversified away from oil and gas.

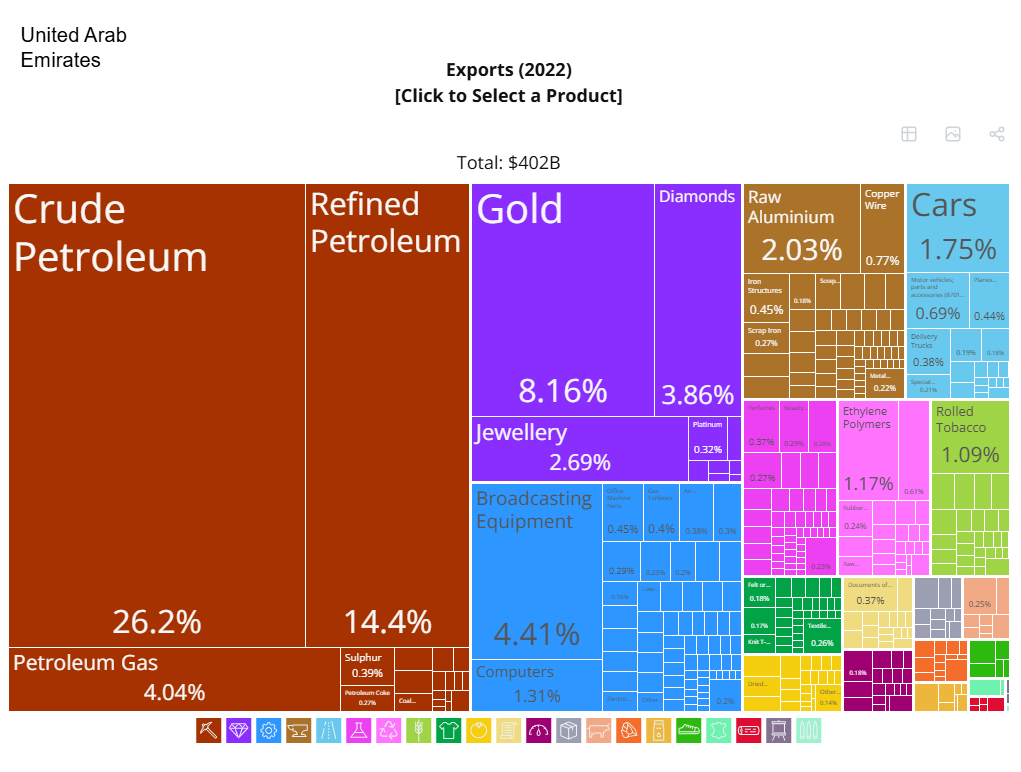

Compare exports from the UAE in 2022

to those from Saudi Arabia.

Gold, to be clear, despite getting a lot of mention in titles of books about the place, is not mined there; it’s showing up as part of the finance/tax evasion/transshipment complex.

Why could the UAE diversify in ways that Saudi Arabia failed to do? It was smaller. 11 million people now in the UAE compared with 32 million in Saudi Arabia, with about 1 million of the former being Emiratis versus about 18 million Saudis. It was less pivotal — Saudi oil has been and remains the linchpin of OPEC, making it particularly hard to distance itself from oildom. It’s very size and non-pivotal nature allowed the UAE to take smaller steps where plausible rather than big swings with misses that Saudi kept on flailing over. Because, to be clear, diversification means explicitly moving away from oil and gas, and in a world needing to undertake an energy transition that is very difficult to contemplate for a petrostate.

But the UAE, through its renewable company Masdar, is interested in more than just participating in conversations about the energy transition: it is hoping to shape them. And not all in ways that fit my preferences, Sultan al Jaber, after all is not just head of Masdar but also of Adnoc, the Abu Dhabi National Oil Corporation. Yet they are moving and making major investments.

They built a large nuclear facility producing about 1/4 of the country’s electricity in carbon free fashion. Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, still burns oil for about a third of its electricity generation. Solar is also booming in the UAE, and a new facility of over 5 GW with 19 GWh of planned storage is also in the cards. There’s much much more to say about big renewable energy megabases, including, hopefully, in my next post.

Weaving Structures Together

We exist inside of the structure of capitalism, but it is not the only structure. Tooze has popularized polycrisis as a term to frame our thinking of what world we are living in at this moment in time. He has argued against ideas that his thinking is devoid of structures or underplays them, poking at his Marxist antagonist Perry Anderson (though the realism here was directly about Mearsheimer):

Real realism is much more difficult. It’s what artists and poets grapple with—how do we describe and respond to reality in all its rich complexity? What’s the political economy of this hotel we’re sitting in? Why these nuts that we are snacking on and not others? There’s nothing simple about any of it, and I think that’s what draws people in—the shared sense that the world is fascinating and not simple at all. That doesn’t mean we’ll never make up our minds, or that we’ll always be indecisive. Or that big social forces like “capitalism” are not in play in building the hotel or bringing us the nuts. It just means that we shouldn’t assume anything is simple to begin with. Lets start with the fact that hotel construction capitalism and nut supply chain capitalism are very different.

And yes, hotel construction capitalism and nut supply chain capitalism are indeed very different, but they are also capitalisms. Tooze attempts to fragment everything into its own narrative line with its own fascinating history. Perhaps though we should think of capitalisms in this way as fractal, not fragmented. Gorgeous complicated structures that may at first appear chaotic, but when you zoom in or zoom out they take familiar shapes and replicate over and over.

And structures are not individual but weave together. My Hopkins colleague Inés Valdez argues in her recent book Democracy and Empire: Labor, Nature, and the Reproduction of Capitalism that you need all of those structures together to understand their collective effect on the world in which we live. And there are many other possibilities about how lives are lived in this world.

Take the following two books

Hannah Ritchie’s Not the End of the World is a fascinating data-centric look at where we stand in 2025, befitting her role as the “lead researcher at Our World in Data.” It’s broadly optimistic and focuses as much on how much things have improved today compared with our past as it does reflect on (or lament) how far we are from where we need to be. Children of a Modest Star, by contrast, is a radical call for the necessity of “planetary thinking,” that is, of thinking beyond the nation-state, in order to address the crises that surround us.

I’m happy both books exist and am perhaps part of a very narrow slice of a Venn diagram of their audiences. In large part because they are engaging in different kinds of politics. The great poaster Liam Bright, aka Last Positivist, had an old post that illuminated a divide I just wrote about when I complained about Bidenism’s failures.

Here are two ideals of openness in inquiry, both of which are independently attractive on both ethical and epistemic grounds.

Per the first ideal, call it openness-to-challenge, scholars are such that their pronouncements are as falsifiable as possible; as much as can be facilitated the scholar renders themselves capable of being shown wrong, if indeed they are. The goal here is to avoid gurus and unchallengable experts. …Per the second ideal, call it openness-to-participation, scholars should be such that their pronouncements can be understood and engaged with by a broad class of people. The ideal here is to avoid esotericism, and ensure that the public have access to knowledge that affects their lives.

Not the End of the World is open to participation. It is digestible, accessible, and relatively transparent in its argumentation and calls to action. Children of a Modest Star is open to challenge. It is well-written but engaging in imaginative thinking about future worlds that are a bit more distant to a more elite audience, with calls to action that are about thinking of habitability rather than sustainability and planet rather than globe. I don’t mean to sound dismissive as I write these words — it’s an important work that has stayed with me and wormed its way into my own analysis.

I think my main concern with the social theorizing that happens is how inaccessible it is as pragmatic politics. I say seeing that at this very moment substack is warning me that this post is “too long for email” and I’ve already traversed so much territory that the descriptor “rangy” doesn’t really cut it.

Maybe I’ll end with the following. A failure of Biden that I didn’t dwell on in the last post is the TikTok ban. Which at this very moment in time is creating an absolutely unintended and unforeseen rush of users to an alternative Chinese platform: Rednote (小红书). The wave of Americans are encountering the existing Chinese user base in fascinating ways, with structures of capitalism and nationalism and censorships and imaginations exploding myths and mythologies and also reinforcing them. Half a decade ago now, something briefly appeared that rhymed with this move. The audio sharing site “clubhouse” was unblocked in China and led to some people-to-people dynamics that are hard to account for in our big structural models of political economy. Perhaps this too is uncertainty in action. Possibilities exist. Let’s seize them.

Incidentally, but probably not, my 7-year-old asked me yesterday “how do you make money?” and after I began to explain jobs and income to him, he interrupted, not earn money but MAKE money, which became a conversation about governments and trust and anti-counterfeitting measures and really felt like we were talking about these rules at a deeper level than we had previously.