Slouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (of Neoliberalism)

A China-centric poke at Brad Delong's Slouching Towards Utopia

Brad Delong writes a lot, he writes well, and he writes on the internet. And so offering a snippet review of one slice of his magnum opus Slouching Towards Utopia, an undoubtedly impressive and absolutely engaging piece of scholarship of the long 20th century, feels a bit like picking a fight with a person who buys (internet) ink by the barrel.1

I want to preface this provocation as distinct from Tooze’s — though, like Tooze, I also have a hard time reading a history of the long twentieth century while ensconced in my position well into a 21st century where it seems increasingly clear that climate and China are central if not the main characters. But also as different from Delong’s colleague Yingyi Qian who similarly wants more China (and India) in the book so that it will appeal in the long durée going forward as well as noting that the “Global South neoliberal turn” was much more successful than that of the Global North.

No, my concern is related but distinct. Delong, who has energetically and honestly asked for criticisms for months, has posted numerous reviews and his commentary on them, many of which lament that the turn to neoliberalism is less clearly, confidently, and coherently accounted for in his model than earlier pieces of the narrative. And while there is perhaps something interesting to plumb there—do we always see more clearly the worlds we emerge into than the worlds we live through and shape ourselves—my intent is different here as well.2

I argue that taking China more seriously as not just a major player in the world going forward but as a causal force in the global turn towards neoliberalism as well as its current demise (?) is a missed opportunity.3 It’s something that I write about briefly in my new book, Seeking Truth and Hiding Facts: Information, Ideology, and Authoritarianism in China.4

I’m not going to offer a full summary of the book when the author literally has a menu of elevator pitches of different lengths available to you on his substack.

I’m fond of his 100 word version (it’s 99 words).

The long 20th century—the first whose history was primarily economic, with the economy not painted scene-backdrop but rather revolutionizing humanity's life every single generation—taught humanity expensive lessons. The most important of them is this: Only a shotgun marriage of Friedrich von Hayek to Karl Polanyi, a marriage blessed by John Maynard Keynes—a marriage that itself has failed its own sustainability tests—have we been able to even slouch towards utopia. Whether we ever justify the full bill run up over the 140 years from 1870 to 2010 will likely depend on whether we remember that lesson.

So, for the “Thirty Glorious Years of Social Democracy” following the end of World War II, “near-utopia came nearer, rapidly.” This phrasing is very common and, in some ways, not wrong. From the depths of destruction wrought by World War II, things got better for most of planet earth. Certainly if one weights significance by economic size, then this was a period of vast improvement, relatively well-distributed. On the other hand, different perspectives (*cough* China *cough*) might view this time period as less congenial.

One could argue that the famine of China’s Great Leap Forward is, next to World War II itself, the second greatest devastation humanity has suffered since the Black Death. Forty million Chinese are killed. Delong obviously does not ignore this momentous event, but it is not his focus nor does it fall neatly into the grand narrative either, and so it is mentioned and then passes quickly. One worries that someone scanning the 600 page tome without an awareness of this moment might miss it altogether. On the other hand, there’s a reference at the start of chapter 13 about “technology and organization” in the 1914-1949 period acting not as “forces to free and enrich” but “to kill and oppress,” but somehow what I can only imagine is supposed to be the global death toll of 50-100 million seems to be attributed to China alone.

Similarly, a not-ignored-but-quickly-glossed discussion of the possibility of global thermonuclear war, with the explosive power that could destroy human civilization in a single round of attack and counter-attack is mentioned but not dwelled upon. And, in the end, this is a work of economic history not counterfactuals, so the non-detonation of such chances in the “Cold War” is hardly something that can be stared at productively for too long, or perhaps more directly, is something that can be squeezed when taking a 1000 page draft into a more manageable 600 pages.

Ok, China. Delong writes “Only two things ultimately rescued China and its economy” — (1) not conquering Taiwan and Hong Kong and (2) Deng Xiaoping. Interestingly, the non-conquest of Taiwan and Hong Kong are causally significant for Delong because they are key sources of early investment into the mainland and help catalyze the rapid industrialization; they help rural China take off, as Jean Oi put it. Presumably, having linguistically and culturally attuned investors aids in smoothing misunderstandings and fostering the trust necessary for individuals with capital to put it at risk in the hopes that the investment will produce returns. However, this perspective is distinct from the role that Hong Kong plays in Huang Yasheng’s book, Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics. For Huang, it is the legal protections afforded by an independent judiciary that make Hong Kong crucial. If Hong Kong had fallen, then access to English common law would have been much harder to come by. The broader Chinese diaspora could have served as the seeds of initial capital and so is less crucial, perhaps.

As for Deng, well, it’s a bit more complicated than Mao = {Communist, bad}, Deng = {capitalist, good}. In my new Seeking Truth and Hiding Facts: Information, Ideology, and Authoritarianism in China, most of two chapters are devoted to this transformation of the regime’s political economy and its aftershocks. Here’s a taste of the argumentation and how these political fights worked out in practice:

By choosing to focus on practice and the concrete results of modernizing agriculture, industry, national defense, and science and technology— the “four modernizations”— as core to its justification, the regime’s center regained its footing. But coming to a broad agreement on the regime’s purpose did not end contestation over its identity. Indeed, conflicts raged over who should rule, how, and why.

But this still slides China into it’s own narrative, a sideshow of the great forces of economics and politics reshaping the world and pushing forward neoliberalism from the social democracy that came before it. And I think more could be done to acknowledge China as an agent in that story with particularly underexamined power.

Here’s one statement of Delong’s key claim (one of the joys for me although I understand that it might be frustrating to others is Delong’s strong style — repetitious, loving of tangents—but also often incredibly direct and channeling the reader’s own likely monologue as if he is explicitly having a conversation with you despite the fact that it’s a pulped dead tree with some splotches on it):

Why? In my view, the greatest cause was the extraordinary pace of rising prosperity during the Thirty Glorious Years, which raised the bar that a political-economic order had to surpass in order to generate broad acceptance. People in the global north had come to expect to see incomes relatively equally distributed (for white guys at least), doubling every generation, and they expected economic uncertainty to be very low, particularly with respect to prices and employment—except on the upside. And people then for some reason required that growth in their incomes be at least as fast as they had expected and that it be stable, or else they would seek reform.

So let’s zoom in a bit. The “30 glorious years” actually end in 1973 in the precise telling, with the oil shock of 1973 being a core piece of the narrative of the need for reform (in the West/Japan). But even before the oil shocks, Delong sneaks in a very interesting couple of sentences on p. 431.

One very powerful factor contributing to this consensus was that after 1973, in Europe and in the United States and in Japan, there was a very sharp slowdown in the rate of productivity and real income growth. Some of it was a consequence of the decision to shift from an economy that polluted more to an economy that attempted to begin the process of environmental cleanup. Cleanup, however, would take decades to make a real difference in people’s lives. Energy diverted away from producing more and into producing cleaner would quickly show up in lower wage increases and profits.

I think this gets some things wrong, some things right, and points to some economistic blind spots. First, democratic societies freely choosing to shift priorities to focus less on “the economy” and more on pollution suggests that those societies valued these harder to quantify negative externalities of industrialized growth than their downsides. Second, “cleanup” does not take decades to make a real difference in people’s lives. Take, for example, urban air pollution, which I wrote about in a prior post.

Policies, whether they be in London following the 1952 smog that killed over 100,000 people or Beijing in 2012 following “airpocalypses” can make immense differences in people experiences and their health. What I think Delong means here is something else, that “cleanup” takes decades to make a real difference in economic aggregates and incomes statistics. Whereas the negative effects of this shift show up more quickly and obviously in the balance sheets of companies and the reporting that shapes the worldviews of economically-minded thinkers, policymakers, and the broader population. Again, for me (and perhaps me alone), this resonates completely with the Chinese reform era experience.

To navigate the political difficulties of transitioning from a set of ideas connected with Maoist utopian communism as the regime’s justification to something that had not just failed, Deng and his compatriots suggested that everyone should “seek truth from facts,” a deft use of a classical Chinese expression that Mao had uttered to undermine Maoism. It would not matter if a particular technique reeked of capitalism if it produced good outcomes. The center instituted a “limited quantified vision” into localities, allowing those who wished to seize their initiative to do so. Some grabbed, some invested, others waited. But overall, as it so often does, rewarding personnel based on a few particular statistics produced excellent performance on them. Over time, again, as it so often does, these quantified systems became gamed and failed to capture the whole story; their negative externalities engulfed them like flames on the Cayuhoga River.

But that’s perhaps too much to lay at the foot of a couple of sentences before the core explanation that is offered. That account — Yom Kippur War —> oil shock 1 and eventually oil shock 2 with lots of fascinating messy politics of expectations in between — is fascinating but does go a bit thin on China’s role.

The left had little to offer at the moment that expectations were high and calls for reform were ringing. But even that is too kind. China, at the precise moment when neoliberalism is rising, doesn’t just signify failure, it is explicitly seen as tossing away fetters keeping itself down.

I take up these arguments at the end of Seeking Truth.

[N]ews trickling out of some of China’s early Reform Era actions supported arguments that giving a greater role to markets was a recipe for growth. In February 1978, the New York Times headlined a piece “China’s New Dialectic: Growth” and stated that “the leadership’s pragmatic program of more worker discipline, better management, higher production, and tighter accounting procedures” would have been “labeled capitalism” a year before. The “ascendance” of Hua Guofeng and Deng Xiaoping had, the Times journalist Fox Butterfield wrote, “rekindled visions American businessmen have had since the days of the Yankee clippers: millions of Chinese customers for American products.” On December 27, 1979, a story on provinces opening up for foreign business was titled “China’s Trade Plan Has a Capitalist Tinge”; by August 14, 1980, a blunter headline had appeared: “China Tries Capitalism, and It Works.”

These early shifts away from Maoist planning helped to cement hegemonic beliefs in markets in the field of economics. The (Chinese) left wasn’t just devoid of ideas, it was actively switching sides.

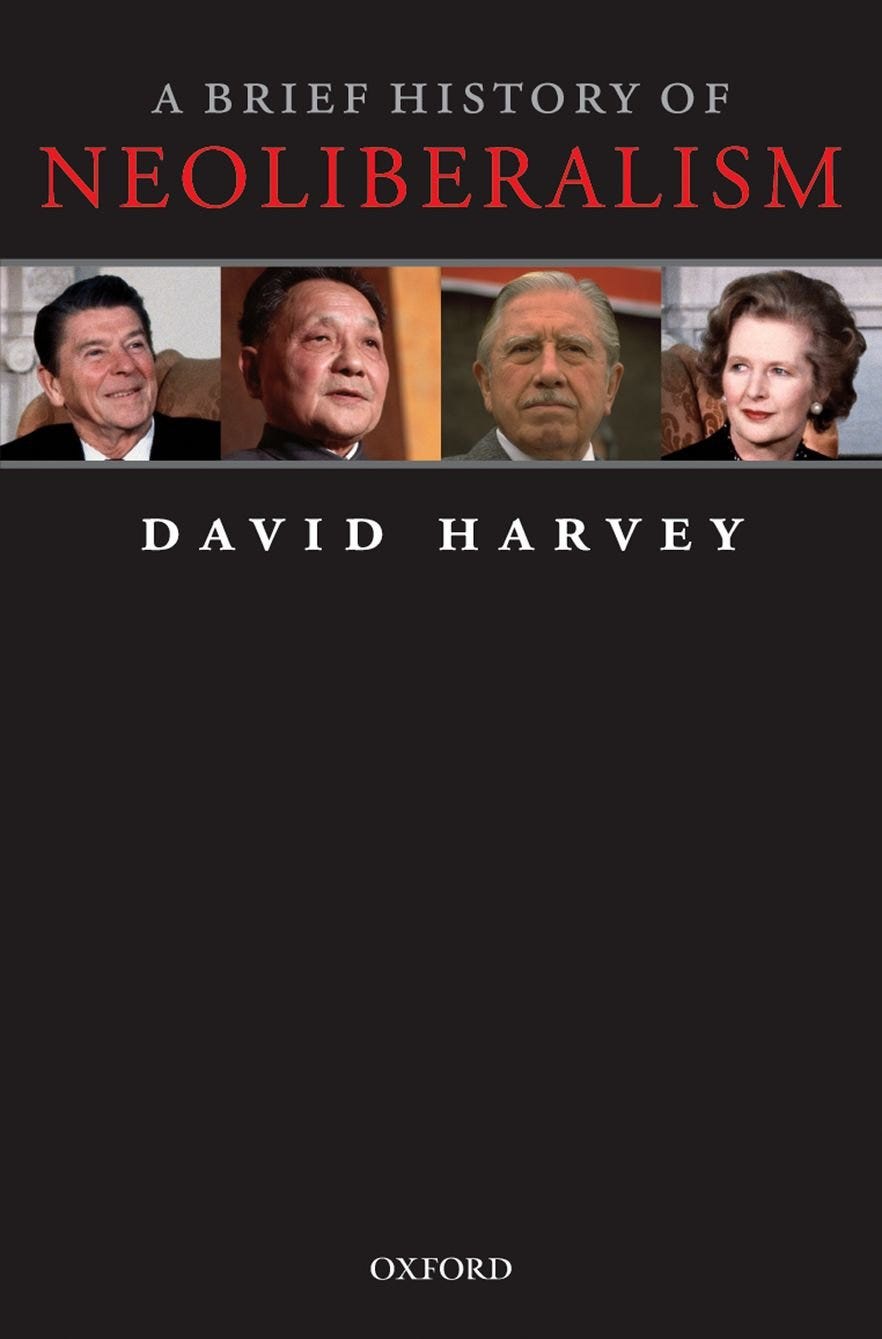

While I have many issues with David Harvey’s neoliberalism book, the fact that Deng Xiaoping is on the cover is not one of them.5

Because just as they were keen to see Chinese consumers as a vast market for their goods, capitalists in the West quickly came to see Chinese workers as a tool to control their own workers. With an open China, the profit possibilities of offshoring production became increasingly difficult to argue against, helping to inculcate the dominance of the narrow view of the corporation’s purpose being maximizing shareholder value.

That rapid development in China was seen by modernization theorists and Western politicians as likely to produce shifts in Chinese political dynamics towards greater freedoms helped provide cover for investments that could have been more tarred as disloyal to the home country. The idea that these investments might have positive political externalities smoothed them individually as well as moves to institutionalize their possibility such as China’s accession to the WTO.

After serving as an example that giving ballast for the intellectual movement of neoliberalism at the moment of its rising hegemony and then giving leverage for the deepening of neoliberalism in corporate worlds, China became a political liability and undermining force for neoliberalism.

To be clear, Delong argues against a simple “China shock” understanding of this dynamic where China stole American jobs leading to backlash: “Hyperglobalization’s principal effect was to cause not a decline in blue-collar jobs but a roll of the wheel from one type of blue-collar job to another—from assembly-line production to truck-driving and pallet-moving distribution, plus, for a while, construction.” Instead, he agrees with Dani Rodrik, arguing “To those groups whose jobs were closing down or who were seeing gates slam shut for paths that previous generations had used for upward mobility, it’s no wonder that globalization seemed like a plausible explanation for their misfortune.” I concur, trade with China generated broad but diffuse benefits, principally through cheaper goods to consumers across a range of products, while the costs of the trade remained relatively narrow but deep, as individual factories shuttered and moved abroad, desolating the towns and rural areas they had supported (“churn” in Delong-speak) even if they did not decimate the working class in aggregate.

China’s undercutting of neoliberalism also comes from its presentation of an alternative system of political economy with substantially more state involvement in the economy, particularly in the form of Keynesian stimulus in dangerous moments (i.e. Global Financial Crisis) and, more generally, of industrial policy for favored firms and sectors. Trends of deglobalization, regional blocs, petro-politics, climate change (and the failure of carbon taxes), and pandemic all seem to be nudging us away from the neoliberalism (certainly of the neoliberalism of the 1980s). Perhaps Delong simply respects his foe of the past four/five decades enough to not count it out just because some punches are beginning to land and it is staggering.

Perhaps I’m over interpreting trends based on my Sino-centric perspective. To be clear, I’m not suggesting that a world shifting away from neoliberalism will be moving more quickly to utopia. While hazy the future remains, it seems as likely as not that we’ll fall deeper into morasses of identity-based violence, isolationism, beggar thy neighbor policies, and war. Perhaps he needed to end it here so that we could still be seen as at least seeking utopia, rather than something darker.

[As I was finishing this I started listening to Delong on the Ezra Klein podcast where they apparently spend the whole time talking about the inflation of the 70s and what it might mean. I can’t listen to that and then edit this in response because when I’m done with that I promise you there will be even more Delong content.]

Perhaps not unsurprisingly for such a dense manuscript, Delong explicitly mentions this idea as well:

“Here I need to issue a warning: The time since the beginning of the neoliberal turn overlaps my career. In it I have played, in a very small way, the roles of intellectual, commentator, thought leader, technocrat, functionary, and Cassandra. I have been deeply and emotionally engaged throughout, as I have worked to advance policies for good and for ill, and as my engagement has alternately sharpened and blurred my judgment. From this point on this book becomes, in part, an argument I am having with my younger selves and with various voices in my head. The historian’s ideal is to see and understand, not advocate and judge. In dealing with post-1980, I try but I do not think I fully succeed.”

I am not debating Delong’s characterization of China in the late nineteenth century here but imagine that some of my colleagues might.

Wait is this review of an actually popular book or a secret advertisement for my book? I’ll never tell.

You’ll have to buy my book to find them out.

One problem with "fault of neo-liberalism" opinions and beliefs is that how to explain all government interventions and expansions during the 2000s?

https://glibe.substack.com/p/neoliberal-2000s-less-liberalisation

Late 19th century China (nit): Delong thinks Port Arthur/Dalian is in Shandong.

I am firmly of the belief that Delong's failure to treat substantially the post-Mao rise of China in the world economy is both a major missed opportunity, and error.